ASLE and the environmental humanities were well-represented at this year’s Modern Language Association meeting in Seattle. Two sessions were sponsored (or co-sponsored) by ASLE, and there were several others with a focus on environmental humanities and ecocritical topics. The following four sessions, reported on by ASLE members who participated in them, showcase the range of environmental topics discussed at the conference.

Revising Resilience: Literary Listening and Indigenous Perspectives

Report by Ned Schaumberg, Pacific Lutheran University

Lydia Heberling (U. of Washington, Seattle), Presider

Participants: Ned Schaumberg (Pacific Lutheran U.), Sage Gerson (U. of California, Santa Barbara), Jasmine Spencer (U. of Victoria), Alyssa Hunziker (Oklahoma State U.)

This ASLE-sponsored panel was organized and conceived to foreground ideas of “listening” to Indigenous texts, especially as they complicate the popular framework of resilience-based thinking in the environmental humanities. Unfortunately, one of the panelists was snowed in, but the loss of a linguistics perspective on the above issues was offset by the vibrant and collegial dialogue between audience and participants that ASLE is known for.

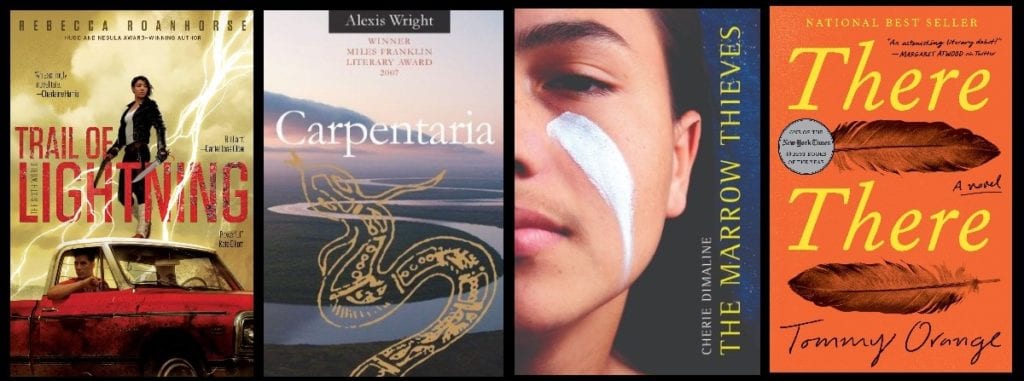

All three papers paid special attention to the complexities of encountering and writing about Indigenous literature as settler scholars. More specifically, each paper offered an environmentally- and culturally-specific reading that pushed on assumptions about what constitutes “Indigenous environmental literature.” Sage Gerson discussed Tommy Orange’s highly regarded There, There, foregrounding the importance of simultaneously considering urban environments and historical contexts as essential to Indigenous identity. Alyssa Hunziker examined the ways Indigenous speculative fiction like Rebecca Roanhorse’s Trail of Lightning and Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves foregrounds the role of both history and cultural tradition in renderings of the so-called climate apocalypse. Ned Schaumberg focused on Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria and its focus on an Indigenous tradition of “reading” the local environment that upsets a simple Indigenous/settler binary while foregrounding Indigenous knowledge systems that can strategically appropriate settler forms.

The Q&A covered a range of topics, notably the role of sovereignty and its political implications in ecocritical readings; efforts to balance between environmentally-specific and globally-conscious thinking in these readings; and an extended discussion involving both panelists and audience members about strategies for bringing texts like these into the classroom and helping students work through the uncomfortable feelings and conversations that can result.

Birds by William Morris (1834-1896). Original from The MET Museum. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

Ecosocialism and the Late Victorians

Report by Frank Palmeri, University of Miami

Florence S. Boos (U. of Iowa), Presider

Participants: Heidi Aijala (U. of Iowa), Jude V. Nixon (Salem State U.), Frank A. Palmeri (U. of Miami)

At the convention of the Modern Language Association in Seattle, ASLE co-sponsored with the William Morris Society a panel on “Late Victorian Ecosocialism.” The three participants presented various approaches to the topic, the first focusing on women writers and the second two on William Morris’s utopian novel, News from Nowhere (1890-91). Speaking on “Ecosocialist Thinking in Late-Century Women’s Fiction,” Heidi Aijala concentrated mostly on the important work of Katharine Glasier (1867-1950), a provincial Fabian who helped found the Independent Labour Party and who combined socialist and environmental concerns in her many books on socialism and in novels such as Tales from the Derbyshire Hills (1907). In “Ecosocialism in William Morris’s News from Nowhere,” Jude Nixon considered the relation between Guest and his guide in Nowhere as parallel to the relation between Dante and Virgil in the Divine Comedy and presented the conclusion of the work as analogous to a religious revelation. Frank Palmeri, in “William Morris’s Ecosocialism: Then and Now,” discussed the context and predecessors of Morris, including Richard Jefferies’ tale of the re-greening of England (After London, 1885), as well as Morris’s influence on countercultures, communes, and Greens in the twentieth century and on post-growth thinking in the twenty-first. His paper will appear later this year in Useful and Beautiful, the newsletter of the William Morris Society.

Spenser, Ecology, and the Dream of a Legible Environment

Report by Steve Mentz, St. John’s University (Presider)

Participants: Joe Campana (Rice U.), Brent Dawson (U. Oregon), Dyani Johns Taff (Ithaca College), Alexander Lowe McAdams (Rice U.), Will Rhodes (U. Iowa), Tiffany Jo Werth (U C Davis)

(c) Manchester City Galleries; Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

We started our beastly session #666 in the hangover slot early Sunday morning with two imperatives: thinking about how Edmund Spenser’s poetic allegories can speak to the challenges of ecocriticism in today’s literally blazing world and also asking how apocalyptic literary fictions can engage with, critique, and perhaps re-imagine our catastrophic present. The half-dozen stirring talks and conversation afterward followed a pattern of looming disaster confronted if perhaps not fully avoided. Joe Campana’s opening talk, “Should (Bleeding) Trees Have Standing?”, explored the legal status of forest lands through the poetic figures of talking trees in and before Spenser. Fantasies that trees might stand as people connected to current legal regimes of nonhuman persons, from rivers in New Zealand to corporations in the United States. Brent Dawson’s “Spenser’s Storms and the Ends of Time” opened the aperture out to competing ways of thinking about time itself, perhaps the knottiest problem both for earth systems ecologists and early modern epic poets. Contrasting the Lucretian clinamen and the Pauline kairos, Dawson showed that Spenser’s multiplicity of chronologies speaks to the overflowing time frames of ecological thinking. Dyani Johns Taff’s talk, “Male Wombs, Ravenous Oceans, and Racialized Environments in The Faerie Queene,” focused our session on the watery horrors of Guyon’s voyage in The Legend of Temperance. Her analysis of the erasure of femininity in Spenser’s depiction of Scylla and Charybdis points toward an exciting new project that will address the much-needed intersections between early modern discourses of ecocriticism and Critical Race Theory. Alexander Lowe McAdams continued discussion of Guyons’ quest with her paper, “Spenser’s Ecology of Temperance.” Her careful unfolding of the shared etymology of time, tempest, and temperance – all from the Latin tempus, which also connects to the French temps, the most common term for the weather – showed how Spenser’s epic recognizes multiple meanings and attitudes toward the partly hostile and partly legible environments into which Spenser’s knight and we ourselves must walk, “while weather serves, and wind” (Faerie Queene 2.12.88.9). Will Rhodes turned our conversation toward Spenser’s involvement with colonialism in “Reading the Colonized Environment: Irish Ecology and Allegorical Landscapes.” His analysis served as a powerful caution that dreams of legibility are also fantasies of colonial control. Finally, Tiffany Jo Werth, the current President of the International Spenser Society, dazzled us with a talk that traveled from the new Jerusalem to Silicon Valley: “Life after Earth: Eschatology and Ecocriticism via Redcrosse Knight’s Vision.” Treating the Knight of Holinesse’s vision of the New Jerusalem as an allegorical parallel to the post-human utopias of California web-culture’s techno-savants, Werth brought our session to a close with both a pointed suggestion – web entrepreneurs should read more Spenser! – and a textured meditation on the ways in which humans have sought and still seek to transcend the limits of fleshy mortality. These papers all contributed to the visions of possibility amid destructive change that, as I have blogged at greater length, were the defining features of MLA 2020.

Empire and Environment: Confronting Ecological Ruination in the Asia-Pacific and North America

Report by Rebecca Hogue, University of California, Davis (Presider)

Participants: Kathleen Gutierrez (U. of California, Berkeley), Rina Chua (U. of British Columbia, Okanagan), Heidi Hong (U. of Southern California), Xiaojing Zhou (U. of the Pacific)

This panel brought together scholars who have collaborated for our forthcoming anthology, Empire and Environment: Confronting Ecological Ruination in Asia-Pacific and the Americas, edited by Rina Chua, Heidi Hong, Xiaojing Zhou, and Jeffrey Santa Ana (The University of Michigan Press). The anthology breaks new ground in ecocriticism regarding content, scope, and approaches and concerns of Asian, Pacific Islander, and North American cultural works in response to the impact of colonialism and imperialism on ecological collapse and the production of environmental knowledge. This interdisciplinary collection offers a diverse array of writings and images that engage with the violent accrual of what Ann Laura Stoler has termed “imperial debris,” which evidences “the wasted matter left over by the project of development” on a planetary scale. Empire and Environment thus illuminates and emphasizes histories of imperialism, colonialism, militarism, and global capitalism to show how these histories are integral to understanding representations of environmental violence that are revealed both as ongoing imperial projects and as imperial debris in the Asia-Pacific region. Subsequently, the authors redefine approaches to the fields of postcolonial ecocriticism and Transpacific studies by proposing alternative decolonial, feminist, indigenous, and queer paradigms of ecological care and relationality that challenge continuing imperialist modes of social dominance and environmental ruin. At MLA, our presentations featured Kathleen Gutierrez’s work on “white space” in colonial intellectual history in the Philippines, Rina Chua’s comparison of Philippine and Canadian ecopoetry, Heidi Hong’s investigation into the ecological afterlives of empire in the Vietnam War, and Xiaojing Zhou’s close reading of Chamorro Ecopoetry as an archive of imperial ruination.