By Bridgitte Barclay, Steven Carter, Angie Lopez, and Blythe Keuning

“Prairie in Illinois” painting by Leslie Gaeta

I’m generally hopeful and teach on the premise that wonder and curiosity can help us engage with the world around us in positive ways. Teaching environmental writing remotely in the pandemic with a broken ankle in the deep Chicagoland winter last spring, though, it was tough to find much to garner hope. Many of us in environmental studies have to practice hopeful caretaking for ourselves and for our students at the best of times, and that has been harder over the last few semesters. Rebecca Solnit writes in “Grounds for Hope” that hope “is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine” but rather “an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists” (32, 33). She compares disaster to revolution in that it is “disruption and improvisation” with “new roles and an unnerving or exhilarating sense that now anything is possible,” especially with the power of solidarity (34, 39). We read this Solnit piece in Environmental Research and Writing: Popular Science and Advocacy in Spring 2021, as well as several other pieces on the power of narrative in creating hope and energy, but, until student projects, I felt like I was teaching things I wanted to believe still. Their ecomedia projects to communicate environmental issues to the public – podcasts, short stories, comics, documentaries, articles, children’s books, paintings, cooking videos, and museum exhibits – demonstrated the “unnerving,” “exhilarating” “new roles,” re-teaching me how powerful narratives are, and they became my source of hope.

Because of the space we were all in in spring 2021 – are still in now – I used effort-based grading approaches to promote creativity and to function as a form of empathy and impetus to grow, to be okay with messing up and trying. And I demonstrated messing up a lot. The grading was deliberately tied in with speculative ecomedia since I asked pre-med, environmental, and English students to make creative projects with environmental themes. I wanted them to be untethered from grades and focused on revision so that they could try new media. Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism resonates with what we all have been doing in these ways. Russell writes about embracing “glitches” as a form of solidarity and resistance: we can “create space through rupture” and the “power of the glitch” is that it is “an error, a mistake, a failure to function” (7) and an “activist prayer, a call to action” (11). As instructors struggle to find hope and dig up the energy to show the care students deserve while teaching in the already often hopeless field of environmental humanities, speculative ecomedia – and my attempts to incorporate creative assignments with it – function as glitch space. (Please note that each of the students who writes below points out how bad I am at creating assigned breakout rooms and that Steven describes group work’s “moderate success.”) Class spaces became glitch spaces where we all found solidarity.

Environmental Studies majors Steven Carter, Angie Lopez, and Blythe Keuning write here about that glitch space with pandemic learning and about creating ecomedia. Their work highlights kinship. Steven’s project on permafrost thawing developed from a podcast to a website with links to other projects. He interviewed scientists from Russia and Alaska, perhaps the only advantage of the Zoom world. Angie wrote a thoughtful, character-driven short story and created a digital comic to go along with it, focusing on environmental justice in a resource-sparse future, asserting a more just world. Blythe made a documentary about her pandemic work establishing a monarch refuge at her house, reflecting on what she learned about herself as well, reminiscent of Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s World of Wonders. Her ecomedia demonstrates that stretch of kin and practice of care. Please take time to check out their work and let them know how much it matters.

Image from Museum Exhibit on Pangolins, illustrated by Melissa Smith

Steven Carter

I just recently returned to school after a long absence to pursue a bachelor’s degree, and I was actually not unhappy about the idea of online classes. I would consider myself a textbook example of an introvert. I liked the idea of just rolling out of bed and going to my computer a heck of a lot better than going in person and having to, you know, talk to people. Many of the things that happen in the classroom were not changed much at all as a result of being online. Lectures were the same, including the students being mostly silent whenever a question is asked.

One thing Dr. Barclay did differently from the other classes I was in was to really try to incorporate group activities. That is something that I think is substantially harder to do on Zoom, but certainly still possible. There were times of chaos, especially trying to put people back into the same breakout room multiple classes in a row. There is also the opportunity for students to just vanish into their black screen, being neither seen nor heard, something that is really tough to pull off in real life. Despite these difficulties, I would call the group activities a moderate success, and I do really appreciate the effort.

For my final project for Dr. Barclay’s class I decided to make a podcast. It’s a medium that I greatly enjoy. I find it amazing to be able to be entertained and learn things in situations that I normally wouldn’t, like going for a walk or driving to work. I chose to make it about permafrost and the threat it’s under from climate change. I’m a bit an environmentalist hipster, so of course I have to do something that not many people are aware of. It was pretty much the same as doing it during a physical class, but I think there was one thing I benefited from everyone being online: I did three different interviews with people from all over the world. Of course the technology to communicate long distances is as old as the telephone is, and even Skype has allowed face-to-face conversations over long distances for a while. But this past year and a half has forced everyone to be able to communicate this way, and it was super helpful for me. I had some really great conversations with people who are among the most knowledgeable in the world about permafrost. Those conversations may have been possible in previous years, but I knew they would be possible under the new Zoom world order.

Being back in class this semester has made me realize that my original thoughts were a bit foolish. Commuting and having to put pants on were a bit of an adjustment, but I’m happy to do it. It was great to meet people who I had only ever seen on a monitor, group work and labs are so much better in person, and doing activities on campus is a lot of fun. And it turns out having to talk to people is really not that bad.

Shannon Sitch’s illustration from Miranda Devan’s children’s book The Condor’s Tale of Conservation

Angie Lopez

Spending my first year of college online was difficult, to put it plainly. Everything became a distraction, a bore, and I felt an absence of connection when joining e-classes. Dr. Barclay’s Environmental Research and Writing class didn’t feel like that, though. I think more than anything Zoom classes became a learning experience for everyone. Messing up breakout rooms, learning to submit items, figuring out how late you could wake up and still look presentable in front of a camera are all important.

For me specifically it was an introduction to college life, a mixture of ideas and philosophies in one virtual classroom, some more science-based, and others more lyrically inclined. I learned how to pay attention in this class, in moments where the neighbor’s bad parking was peak entertainment, I learned how to look at the world with greener lenses, when the sky only seemed to play the same five shades of gray. The number of times I had to untangle my brain after reading about slow violence or ecofascism [and this] and the number of times Dr. Barclay has made me believe there is hope in a world more intense than I first naively thought.

I wrote a short story for my final project. It’s something I had always wanted to do but was too scared to try, and this class allowed me to without feeling like my grades would be in jeopardy. Dr. Barclay’s grading system allows for mistakes, encourages creativity, and motivates students to try new things. The story was about two sisters living in a bubble, literally and metaphorically, where grief sparks action. It was more about the catalyst or moment we take a stand than what follows. So often we forget that there is a beginning to movements, that there is grief in realization, and power in love and loss.

Reading is one of my favorite activities. It’s one of the things that has shaped my thinking and made me empathetic. Writing, to me, was what I imagine running is to a track star: painful in the best ways and necessary for no else other than me. Still the characters and settings, although plenty, never seemed to fit the perfect story, and this final project gave me the perfect excuse to give them a test run. If you’ve ever seen Whisper of the Heart by Studio Ghibli, you’ll understand the feeling of writing your first story – a glorious moment followed by anxiety when you realize you have to share it with the world. You read and read and find more and more mistakes to your story, to your characters, to your writing.

But, putting these final projects in a forum, where other students could read and comment on your writing, was both a stressful and eye-opening experience for me. The comments were wonderful, I received so much positive feedback, and some even made connections to things that I hadn’t even noticed. The point of all of this is that the class opened up new ways of thinking for me, left me with more questions than answers, but with endless curiosity and vigor to explore nature and my place in it.

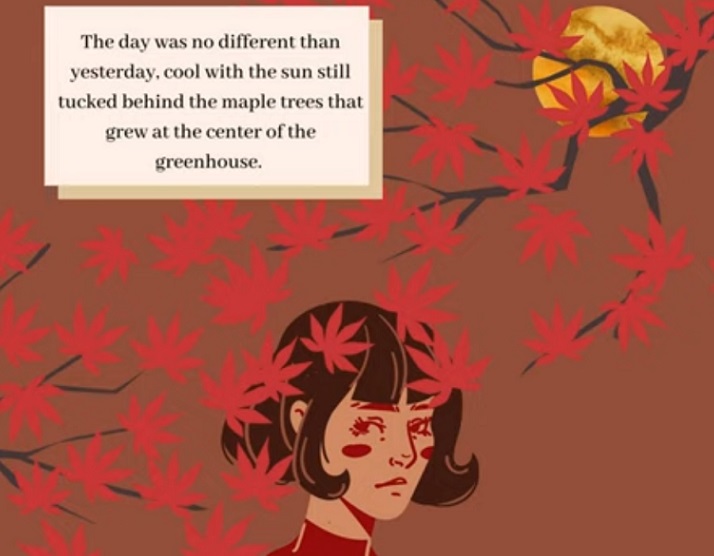

“Falling of the Leaves” comic via Canvas by Angie Lopez

Blythe Keuning

Through the examples of ecomedia covered in class, Dr. Barclay emphasized that the most effective tool in environmental writing was inspiring empathy through connection. It was this concept that I used as a foundation in designing my final project: a short documentary film about the monarch butterfly. After I began making my documentary, an exploration into connection, I realized I would need to include more than just information about the monarch life cycle and reasons for their declining population. If I wanted to inspire empathy, I would need to explain my own personal connection to monarchs and the emotional significance they have for me. I deeply struggled with this realization; sharing intimate details of my personal life in the documentary felt vulnerable and scary. But if I was going to make this documentary, I wanted to do it right.

Screenshot from Blythe Keuning’s The Monarch Mission

Connection is essential for the human experience; its importance cannot be stressed enough. Healthy social connections foster better physical health as well as mental health, helping us to regulate our emotions and decreasing anxiety and depression. They can lead to higher self-esteem and can improve our ability to empathize with others. Connection leads to empathy, and empathy can inspire and spark action. This is essential to tackling environmental issues, because finding solutions requires action. In the midst of a global pandemic with the subsequent lockdowns, and in a world that felt void of human connection, it felt both ironic and perfectly serendipitous that I needed to create a final project that should inspire empathy through connection.

In situations causing extreme physical or emotional distress, the human mind will distance itself, forming a mental separation from the threat. This subconscious dissociation is a coping mechanism – self-preservation at its finest. When the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread across the globe, the physical separation from lockdowns was quickly followed by an emotional separation. When faced with the utter horror of our situation, our minds shut down. Disengaged. Disconnected. In a world full of disconnection, how do we begin the daunting task of reconnection?

I am no stranger to disconnection caused by extreme distress; I am a survivor of childhood trauma and have spent a lifetime struggling with the resulting anxiety and depression. Feeling lost in the darkness of my trauma, I searched for an emotional escape in the natural world. I would frequently go hiking in nearby prairies and forest preserves; and after buying my own home, I would work diligently for long hours in my garden. A couple of years pre-pandemic, I began raising a small number of monarch caterpillars that I found in my garden. My work with the monarchs brought me endless joy and made me realize that like the monarch butterfly, I also went through a transformation. I pulled strength and inspiration to share my story in the documentary from one of my favorite authors, Brené Brown. In her book The Gifts of Imperfection, she said, “Owning our story can be hard but not nearly as difficult as spending our lives running from it. Embracing our vulnerabilities is risky but not nearly as dangerous as giving up on love and belonging and joy—the experiences that make us the most vulnerable. Only when we are brave enough to explore the darkness will we discover the infinite power of our light.”

In my search for an emotional escape from the darkness of my trauma, I found the light of empathy and connection. I embraced the vulnerability it caused and poured my story into the documentary. I have never been so proud and excited to turn in a homework assignment.

Screenshot from Blythe Keuning’s The Monarch Mission

Conclusion

In my teaching and writing, I always come back to Donna Haraway’s notion of making kin and the argument by Stacy Alaimo, my friend and mentor in studies and in life, that “if we cannot laugh, we will not desire the revolution” (3). I have realized these last few semesters how much community I need with students in order to feel that solidarity for a larger sense of hope. I used to take laughing with them, them laughing at me, for granted. But working for empathy through playful wonder, curiosity, and community are essential to environmental studies – even more so now. Consider this a letter of gratitude to my students, especially Steven, Angie, and Blythe.

ENV/ ENG 3811, Environmental Research and Writing: Popular Science and Advocacy, met in Spring 2021 remotely via Zoom. Steven enjoyed introvert-friendly college from afar; Angie wowed everyone, even in her first year; Blythe helped Bridgitte figure out where to place the dying ivy in her Zoom background; and Bridgitte hobbled around on crutches. All are reunited in another environmental course this year, and Steven, Angie, and Blythe continue to teach Bridgitte.

ENV/ ENG 3811, Environmental Research and Writing: Popular Science and Advocacy, met in Spring 2021 remotely via Zoom. Steven enjoyed introvert-friendly college from afar; Angie wowed everyone, even in her first year; Blythe helped Bridgitte figure out where to place the dying ivy in her Zoom background; and Bridgitte hobbled around on crutches. All are reunited in another environmental course this year, and Steven, Angie, and Blythe continue to teach Bridgitte.