By Timothy Sweet

Extinction studies in humanities disciplines have focused on the scholarship of witness. They ask, When a species becomes extinct, what goes out of the world? Books like Thom van Dooren’s Flight Ways and Extinction Studies (edited by van Dooren, Deborah Bird Rose, and Matthew Chrulew) answer this question with deep and moving case studies. Ursula Heise’s Imagining Extinction shows how such accounts of witness and other biodiversity narratives take shape in various genres.

Extinction and the Human reverses the angle of inquiry to focus on the human side of such cases, specifically the problem of human exceptionalism. In an earlier book, American Georgics, I began an investigation of humans as environment shapers by investigating differences between pastoral and georgic ways of being in the world. I argued that regardless of pastoral fantasies of harmony with nature, we always engage with the world to produce our life and culture. The big question is, How? Early American economic and agricultural writing tried to work out what it meant to be directed by nature in those engagements.

Carrying a similar set of questions through to the present project, I observed that responses to biodiversity loss, species endangerment, and extinction have varied historically. What can these variations tell us about our human being? How do we understand ourselves as one animal among others, but with differences from those others? I wanted to imagine difference without dualism, following Val Plumwood, but of course the historical cases don’t all turn out that way.

Carrying a similar set of questions through to the present project, I observed that responses to biodiversity loss, species endangerment, and extinction have varied historically. What can these variations tell us about our human being? How do we understand ourselves as one animal among others, but with differences from those others? I wanted to imagine difference without dualism, following Val Plumwood, but of course the historical cases don’t all turn out that way.

I can’t help but ask these questions from a post-Enlightenment standpoint, while remaining aware that, as Bruno Latour puts it, we have never been modern. That is, modernity has never succeeded in separating nature from culture, animal from human, fact from value. I put that post-Enlightenment position into dialogue with Indigenous American positions. And I investigated Euro-American positions prior to the Enlightenment as well.

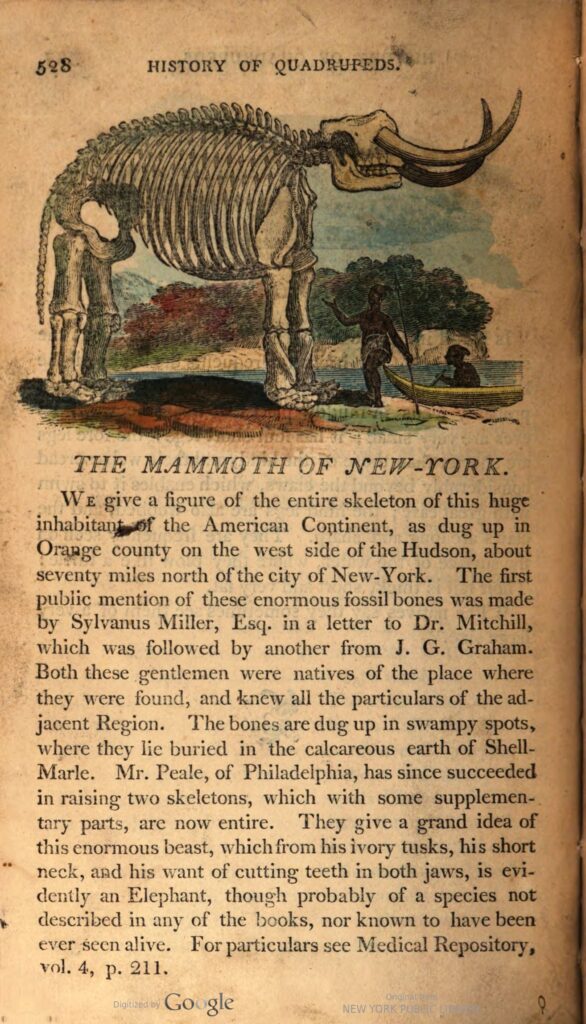

One way to do this, I thought, was to focus on stories about megafauna – big, charismatic beings. Not that bees and coral polyps aren’t important, but megafauna seemed like a more approachable subject. For one thing, they are highly visible as ecosystem shapers. Mammoths and mastodons, for example, kept forests in check to produce varied kinds of savannah and woodland environments. Their extinction in North America and the subsequent growth of forests may have enabled the passenger pigeon to flourish in the massive numbers that early settler colonists observed. More recently in geological time, buffalo cultivated the prairie ecosystem, until they were hunted to near-extinction in the nineteenth century.

As a humanities scholar, I was drawn to the deep archives that megafauna have inspired in vernacular and scientific genres. Smaller species are often less culturally visible. For example, the extinction of Bachman’s warbler was a significant loss, and the recovery of Kirtland’s warbler is a great boon (unless you were one of the brown-headed cowbirds who was killed to enable that recovery). But there aren’t a lot of stories about these species beyond the conservation literature itself. Mammoths, whales, and buffalo, on the other hand, have gained substantial attention from lots of storytellers, popular and literary as well as scientific.

Originally the manuscript included a chapter on Neanderthals, in which I observed that our characterization of Neanderthals has become progressively more humanlike since the first discovery of their remains in 1856. I don’t have space to write about that here – I’m working on a separate essay – but I will recommend reading The Inheritors, the novel William Golding wrote just after Lord of the Flies. It’s a remarkable experiment in narrative point of view.

Cutting the Neanderthal chapter enabled me to focus entirely on the Americas, structuring the book around implicit or explicit dialogues between peoples descended from the two great waves of human migration – the first during the late Pleistocene epoch, some 35,000 to 15,000 years ago, and the second beginning in 1492. This meant, among other points, addressing the problematic “ecological Indian” motif and investigating how Indigenous authors such as Joseph Nicolar directed megafaunal extinction narratives toward anticolonial ends.

“New York Mammoth,” engraving by Alexander Anderson, General History of Quadrupeds (New York, 1804).

Given the book’s long chronology, it’s fair to ask: could Indigenous stories about mammoths really preserve ancestral memory from 10,000 years ago? Lakota activist Vine Deloria, Jr., would have said absolutely yes. Pawnee historian Roger Echo-Hawk would more cautiously say, quite possibly, in some way. Moreover, every story is a product of its immediate context, whether told by a Lenape delegation to the governor of Virginia or by a scientist in a Smithsonian Institution annual report. Context shapes the story’s understanding and assessment of species endangerment or extinction.

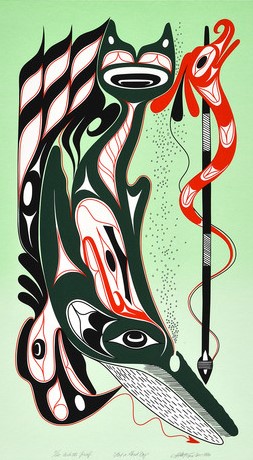

“Not a Good Day,” print by Art Thompson (Ditidaht/Nuu-chah-nulth/Cowichan). Used with permission of Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

The dialogues begin as early as the sixteenth century, with Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s memoir of the conquest of Mexico and José de Acosta’s Natural and Moral History of the Indies. At that time, both Indigenous Americans and Europeans regarded mastodon bones as the remains of barbarian giants. The book’s chronology continues through the present day, for example with accounts of tribal buffalo projects and the Makah nation’s efforts to resume their whale-hunting tradition.

The 1999 Makah whale hunt is an example of how the dialogues don’t always line up neatly as Indigenous versus settler-colonial. The account of the hunt given in Nuu-chah-nulth scholar Charlotte Coté’s Spirits of our Whaling Ancestors and Makah sources is very different from the account given by Chickasaw novelist Linda Hogan in interviews and in her novel People of the Whale.

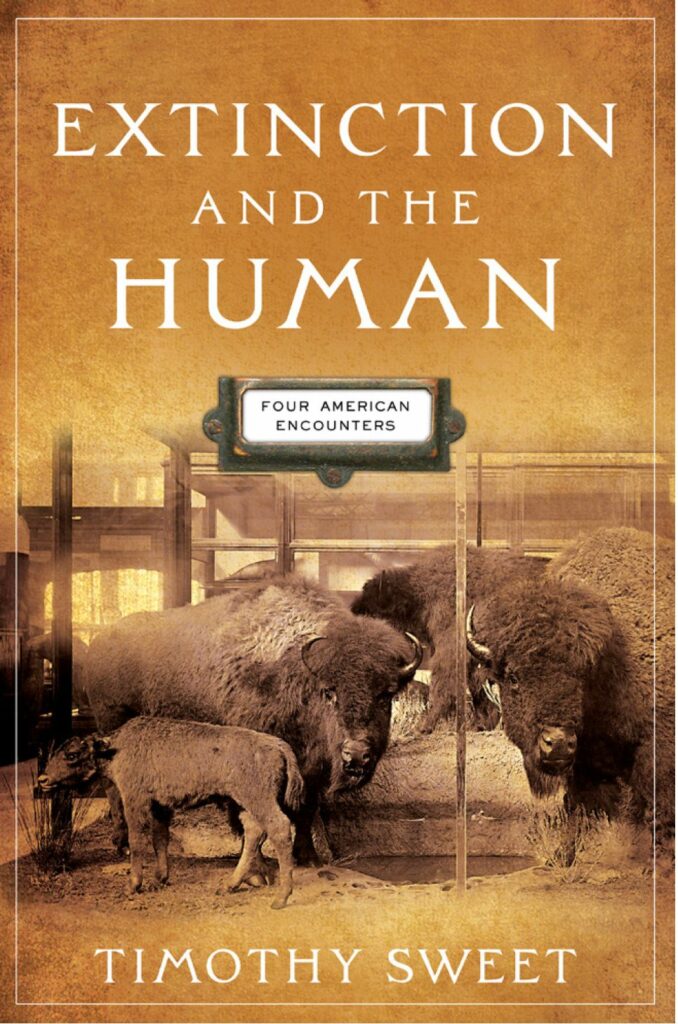

Often, of course, there is direct opposition, as the case of the buffalo. Here white market hunters, abetted by the expansion of the railroads, hunted the buffalo to near extinction by the 1880s. However, preservationists such as William T. Hornaday told a racially bifurcated moral narrative. Hornaday blamed Indigenous people for “wasteful” hunting and said that the people’s starvation after the loss of the buffalo was the buffalo’s revenge. On the other hand, Hornaday saw his own taxidermic preservation of “perfect specimens” as “atonement” for the slaughter. (His “Life Group of American Buffaloes” for the Smithsonian is my book’s cover image.) Where market hunters treated the Great Plains as a Lockean commons, a source of free natural capital, stories by Blackfoot narrators and the Lakota holy man Black Elk developed counter-narratives of equitable access. These counter-narratives have become manifest in tribal buffalo projects.

I imagine dialogues at the theoretical level as well. I set up one such thread by exploring the political implications of Aldo Leopold’s idea of humans as citizens of biotic communities. Latour formalizes Leopold’s political language in the idea of a “parliament of things” in which nonhumans can communicate their interests through scientific “speech prostheses.” Here I suggest a dialogue with Indigenous practices of treaties with animals, which similarly depend on clear communication of interests. Unlike “biophilia,” the instinctive love for nonhumans that Edward O. Wilson hopes will preserve biodiversity, treaties organize environmental relations as political relations. Treaties recognize histories of violence. They are founded not on love but on sovereignty and mutual respect. Without politics, no amount of love will preserve biodiversity.

The Last of the Buffalo (1888) by Albert Bierstadt. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Gift of Mary Stewart Bierstadt [Mrs. Albert Bierstadt]).

Timothy Sweet is Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of American Literature at West Virginia University. In addition to Extinction and the Human, his books include American Georgics: Economy and Environment in Early American Literature (2002), Traces of War: Poetry, Photography, and the Crisis of the Union (1990), and an edited collection, Literary Cultures of the Civil War. He served on the editorial advisory board of ISLE from 2003 to 2020.

Timothy Sweet is Eberly Family Distinguished Professor of American Literature at West Virginia University. In addition to Extinction and the Human, his books include American Georgics: Economy and Environment in Early American Literature (2002), Traces of War: Poetry, Photography, and the Crisis of the Union (1990), and an edited collection, Literary Cultures of the Civil War. He served on the editorial advisory board of ISLE from 2003 to 2020.