By Mika Kennedy, Visiting Assistant Professor in English, Kalamazoo College, with Alyssa Zino, Emily Braunohler, Hannah Shiner, Koyan Sidibé, Lillian Mattern, Matthew, Nikoli Nickson, Preston Grossling, Rachel Madar, and Riley Gabriel

Nature journals are a common and often powerful assignment in environmental humanities courses. Both creative and analytic, they might conjure images of deftly penciled birds, or leaves of grass examined in minute and material detail, and then as metaphor. In Winter 2021, during a pandemic, with students in and out of quarantine – Michigan having avoided the holiday COVID swell only to gradually unravel as our term went on – “nature” and nature journaling needed to mean something different.

Of course, in many ways, it always and already did: Our course was titled “Race, the City, and Environmental Justice” and focused on urban environments. We opened with Emily Witt’s “Miami Party Boom,” which is a little bit about swamplands and hurricanes and a lot about predatory real estate ventures and houselessness. This, we paired with William Cronon’s seminal piece “The Trouble with Wilderness.” One of the points Cronon makes at the end of his essay has to do with home, too: Find the nature at home. For our class, “nature at home” meant not only trading the spectacle of mountains majesty for city parks and backyard trees, but also recognizing our interior spaces as environments worthy of contemplation and observation–as well as recognizing our interiorities as vital elements of these environments.

I had the experience / but missed the meaning

I wanted to use these journals as an experiment in slowing down and opening up space to wander, whether students chose to explore the outdoors or their bedrooms. Introducing the assignment, I wrote,

The planet is going through a lot right now. You might have noticed this. You may, in fact, be altogether too keenly aware. But awareness is finicky, in that too many stimuli can overwhelm and then numb. The poet T.S. Eliot, who penned The Waste Land, describes this phenomenon well with the lines “I had the experience / but missed the meaning.” The fact is, we don’t notice as much as we think. When things get hectic, our brains drop entire wavelengths just to keep us afloat. Too many things, all at once, and our capacity for deep engagement, wandering thoughts, and intentional experience begins to erode. This journal is intended as a permission slip: To be still, observant, and un-rushed for at least a little bit of time each week.

Since the backbone of our class was about defining nature broadly, the only real stipulation I offered was to take the time and make it count for 40 minutes a week. That, and the journals had to be analog. No screens allowed (and/or permission to be free of them, for a breath).

After doing an in-class session to acclimate everyone to the idea of Nature Journals and the different interpretations one might take, students had the option of turning in a Nature Journal during any 5 weeks of our 10-week quarter. Every Monday, students had the option to talk about their recent Nature Journal during class. This allowed students space to draw inspiration from one another and share explorations or experiences they were proud of/had enjoyed, if they felt so moved. I wanted to make sure that the Nature Journals didn’t feel like an afterthought or busywork, but instead like an alternative mode of thinking with concepts we’d be discussing through our readings. Creating space for the journals to come into our regular class time felt like a good way of keeping them in mind while still allowing my students flexibility around how much they felt comfortable sharing.

What is a Nature Journal?

With their permission, I wanted to share a few examples of what these journals looked like, and the multiple forms they took:

Nikoli Nickson reflected on a walk through Kalamazoo’s arboretum in wintertime. Blending the observational and philosophical, he thinks about how seeming unpredictability at the micro-level can look like order at a macro scale.

![Handwritten journal titled "A Walk Through the Arboretum." It includes some sketches of trees, in addition to the student's writing: "For my nature journal this week, I'm taking time to reflect on the time I spent walking through the Arboretum today. It was snowy and the entire landscape was either dark grey (from bark of trees/branches) or white (from snow). In this sense, I feel like I experienced this space in a new light because I'm so used to everything being green + plants/flowers being abundant. I began noticing how everything around me seemed to be randomly formed but still under this broader sense of order. Here's what I mean: [two sketches of trees] Let me explain: when you look up close at any particular tree, the branches seem to have grown in whatever way they want; if I were to watch the ranches grow, I would have no way of accurately knowing what it might look like. In this sense, the close-up is chaotic. On he other hand, when I looked across Bonnie-Castle Lake. The contrast between the gray sky and the black treeline was clear. Despite their close-up differences, all of the trees hit their maximum height at approximately the same point. I noticed this to be true for trees throughout the arb and for other types of vegetation as well, including underbrush and weeds. All of these were of different species, too. I found this to be paradoxical. How could things seem so unpredictable on the micro-level and yet seemed to then make more sense on the macro-level. I then thought about this in my own life and the way in which things can be hectic + unpredictable from day-to-day but usually end up working out in the end. Why is this so? What stops things from never making sense, or never having an element of predictability? Or, alternatively, is there an absence of predictability in general and I'm just human trying to find a rational pattern?"](https://www.asle.org/wp-content/uploads/Nikoli-791x1024.jpg)

Preston Grossling stayed indoors, choosing to experiment with watercolors to paint the icicles forming on his window and to think about watercolor as medium, his tools, and what it means to pursue an art form you love but don’t necessarily feel good at.

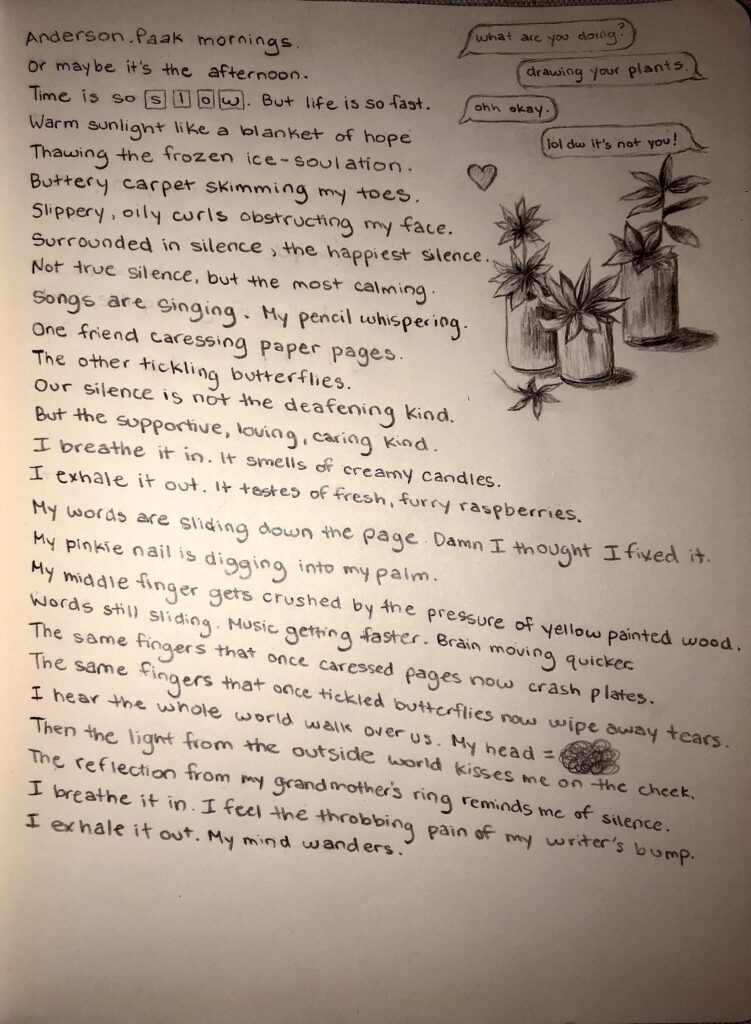

Koyan Sidibé opted for prose poetry, blending the digital and analog by using pencil to sketch both the still life around her – potted plants – as well as the text message conversation that grew up around the plants: “Our silence is not the deafening kind. / But the supportive, loving, caring kind.”

Alyssa Zino chose to visualize stream of consciousness thoughts in the form of tea bag tags, using the small spaces to make fleeting observations about the outside; memories that bounce into view; and questions, reflections, and even intrusions (“oops i checked my phone”).

![Drawing of tea bags with text in them: "sitting on my bed and drinking cold tea," "watching the new neighbors move in," "to the house with the biggest icicles i've ever seen" (decorated with icicles), "the last time i saw icicles like these i was," "in the car with my dad and i pointed them out and he said," "that means they have poor insulation," "but i don't think it was the house that," "had a problem...", "little boy next door is dancing in front of," "the window in the living room," oops i checked my phone," "maybe they should buy some," "blinds [drawn with dark lines like blinds across it]," "or i could spend less time staring," "the definition of mixed feelings is SUNDAY"](https://www.asle.org/wp-content/uploads/Alyssa_Page_1-791x1024.jpg)

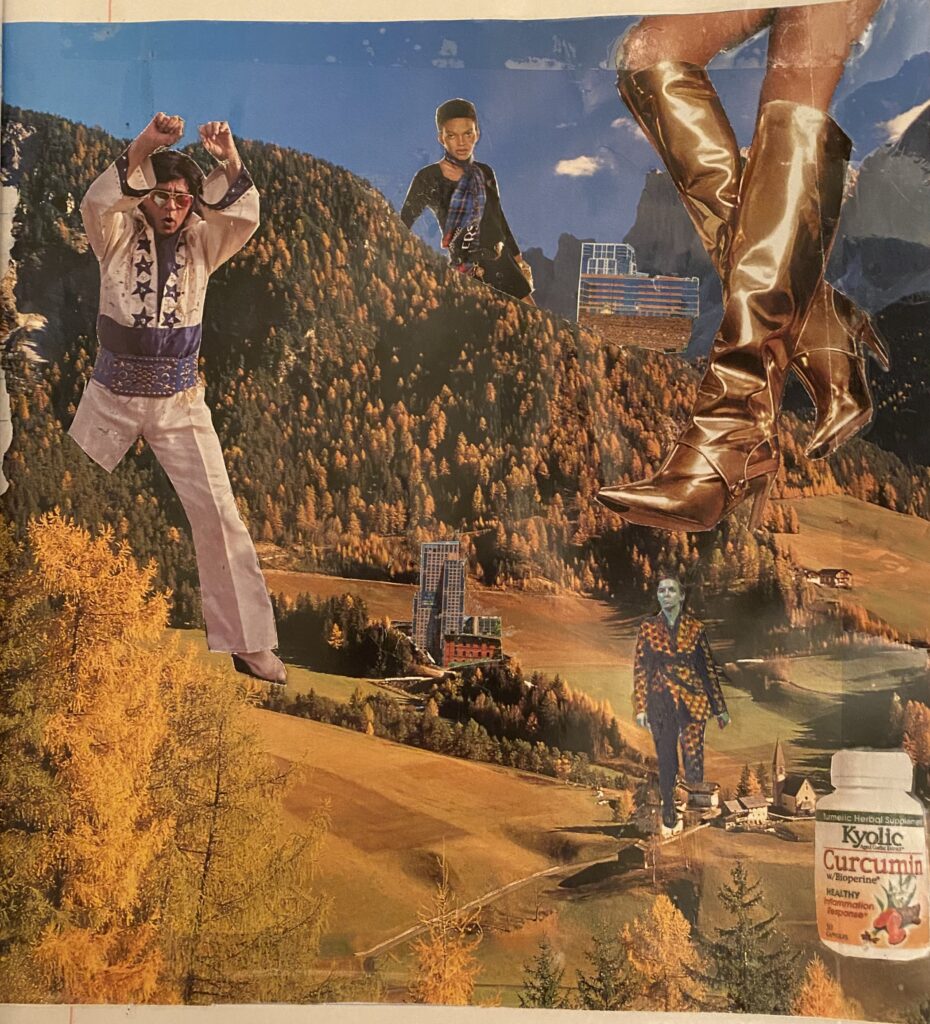

Lillian Mattern prefaced one of her entries as “what I feel in the moment and where I would like my mind to be.” She also created a collage that juxtaposed the traditionally natural and unnatural “to try and perceive them as one, even though they look so different.”

Matthew, who starred in Kalamazoo College’s winter play, completed one of his Nature Journals while rehearsing on stage, making observations of the environment of the theater – a place made up to be another place, and the rehearsal functioning as a place to practice pretending to be in that place.

![Handwritten journal page: "I guess this is still a nature journal so I should maybe write something natrey. How do we describe nature? **Seeing trees **hearing birds **feeling the wind **watching the sunset **seeing a beautiful vista. [Brackets connecting all of these] can be recreated in the festival playhouse. [New paragraph] One would argue that all of this in the Playhouse is fake but isn't the encompassing part of nature that you are comfortable and its all about chasing a feeling? I would argue that the feeling that a good show gives you could be the same that the natural world gives you. Maybe just cause I like theatre but I think both can be very powerful. Nature, Theatre = emotion. [Drawings of sad and happy theater masks] Yay TECH is over."](https://www.asle.org/wp-content/uploads/Matthew-3.png)

What did it mean?

At the midpoint of our Nature Journaling, we held a Midterm Workshop where I split the class into randomized small groups. Each student chose an entry they felt comfortable sharing with the class, and were invited to read and consider each other’s entries before the workshop. Then, in class, we split into small groups, and each group spent around 30 minutes sharing reactions to each other’s entries; seeking trending themes or patterns; and identifying the different approaches each group member had taken with their journal entry. At the end of the workshop, they brainstormed new directions towards which they might take their Nature Journals – forms to try, actions to take, questions to ask.

One of my students, Riley Gabriel, expressed the reassurance they found in hearing that others were also “struggling a bit to stay present. That is something that I have had a hard time with since lock downs started in the US … hearing from everyone else that they were having a similar experience felt good.” Many students used their Nature Journals as a grounding exercise, and a space to manage anxieties, and to take time away from the relentless march of the quarter to be present in the moment.

Hannah Shiner was struck by the range of approaches everyone in her group had taken, which she said “made me consider all the different techniques that can ‘count’ as journaling. It also realized that everyone’s brains work so differently.” Rachel Madar made a similar observation, explaining how a group member was “able to look at the reflection of her light and connect it all the way back to spending quality time with family. This stood out to me because so far I’ve mostly been observing what I’m seeing and the purpose it might have, but I haven’t tied it back into my own personal life as much.”

Emily Braunohler noted that reading and reflecting on each other’s journals “made our groups feel close” and served as a “reminder that it is very important to be vulnerable around people,” bridging some of the alienation and segmentation of virtual learning. This, in turn, allowed for new orientations towards one’s own work: Nikoli Nickson shared that he initially “came into this expecting to be critiqued – similar to my feeling about every other class right now.” What the conversations ultimately emphasized, however, was not critique but listening and exploration. This didn’t mean that there was no rigor to the conversation. Nikoli commended his group for “taking this exercise seriously and for providing valuable insight,” particularly in a form so different than the normative ways we often engage with each other’s work in an academic setting.

Final Thoughts

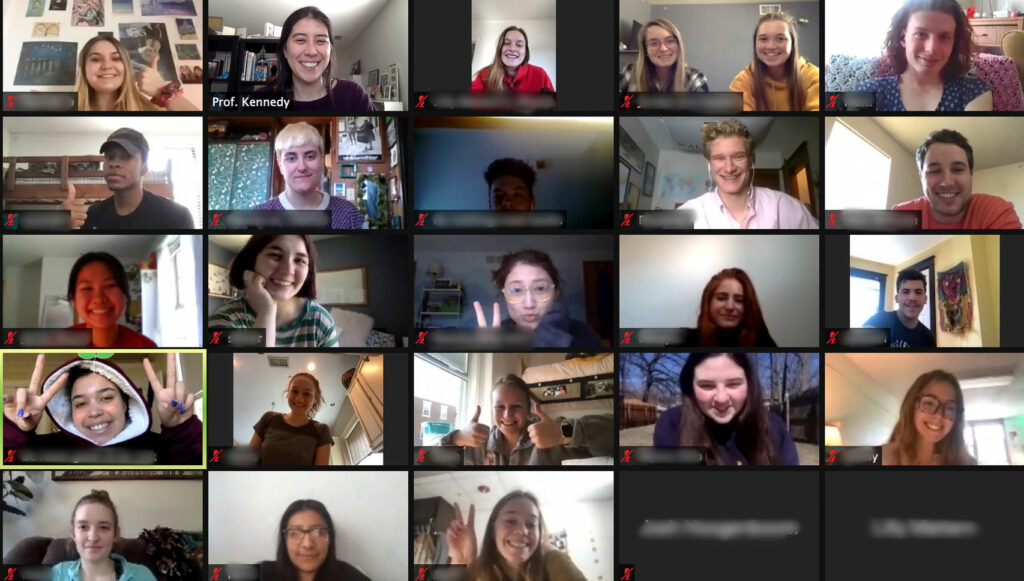

Although a Zoom classroom may not seem like the ideal circumstances for an analog, experiential activity like nature journaling, I think these kinds of practices become even more important. They bring the classroom off the page and invite creative experimentation that augments learning by allowing students to make theories (like Cronon’s) actionable. They open spaces for students to know each other in new ways and feel comfort in engaging in discussion online. They return students to their own bodies.

I see my part in having laid the groundwork for these explorations through the scaffolding I offered: To offer both informal and structure opportunities to connect with each other through these journals and to invite my students to take just as seriously work that is intended to be experimental/reflective as we do our more traditional, scholarly work. The greater part, of course, belongs to my students’ willingness to give themselves to their writing. I learned so much from and about my students through their journals, and I owe this to their investment in the activity, of making use of the space to truly find their natures at home. All my thanks to them!

Resources

Kalamazoo College’s ENGL 151 “Reading the World – Environments: Race, the City, and Environmental Justice” course met on Zoom Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings during the Winter 2021 term, from places as far west as Los Angeles, as far south as Texas, and as far east as Detroit.

Kalamazoo College’s ENGL 151 “Reading the World – Environments: Race, the City, and Environmental Justice” course met on Zoom Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings during the Winter 2021 term, from places as far west as Los Angeles, as far south as Texas, and as far east as Detroit.