By Alenda Chang

When I was in graduate school, a friend who already had school-age children recommended that I read Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods. In it, Louv essentially diagnoses people born from the 1970s onwards with “nature-deficit disorder,” a lamentable lack of connection to the natural environment engendered by television, electronic devices, and gated communities, among other culprits. I remember being sympathetic to Louv’s claims, having spent many carefree hours as a child wandering in the woods around my suburban development, following creeks until they became rivers, building dams, and filling my socks with silt, all without adult supervision. But – I had also spent plenty of time hooked into early online and computing culture, writing collaboratively with strangers on a bulletin board system (BBS), and playing games off 5¼-inch and 3½-inch diskettes (and later SEGA and Nintendo cartridges).

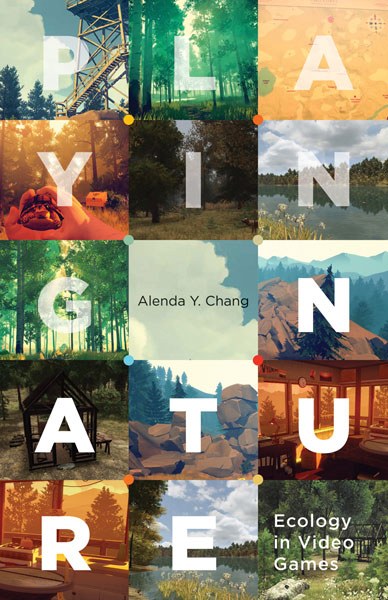

In retrospect, perhaps it’s no surprise that my first book, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games, ended up examining this perennially murky space between nature and technology. While acknowledging the deleterious impacts of game hardware and software production, not to mention energy use, I also wanted Playing Nature to pay tribute to games’ capacity to inspire wonder, curiosity, and emotional investment in designed worlds. As someone who has always been drawn to the life sciences, I was emboldened to put games and game studies in conversation with both science and technology studies (STS) and ecology and environmental studies. After all, games and ecosystems may be productively approached in similar ways. Each of the book’s chapters, for instance, is organized around a scientific or science-adjacent concept that I hope illuminates underexamined aspects of games: edge effects, mesocosms, scale, the nonhuman, entropy, and collapse. Games – whether they are on computers, consoles, or mobile devices, digital or analog, explicitly educational or not – inevitably enact certain kinds of relations between players and imagined worlds and, at their most powerful, they not only mirror our own assumptions about natural environments but work to challenge them.

In retrospect, perhaps it’s no surprise that my first book, Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games, ended up examining this perennially murky space between nature and technology. While acknowledging the deleterious impacts of game hardware and software production, not to mention energy use, I also wanted Playing Nature to pay tribute to games’ capacity to inspire wonder, curiosity, and emotional investment in designed worlds. As someone who has always been drawn to the life sciences, I was emboldened to put games and game studies in conversation with both science and technology studies (STS) and ecology and environmental studies. After all, games and ecosystems may be productively approached in similar ways. Each of the book’s chapters, for instance, is organized around a scientific or science-adjacent concept that I hope illuminates underexamined aspects of games: edge effects, mesocosms, scale, the nonhuman, entropy, and collapse. Games – whether they are on computers, consoles, or mobile devices, digital or analog, explicitly educational or not – inevitably enact certain kinds of relations between players and imagined worlds and, at their most powerful, they not only mirror our own assumptions about natural environments but work to challenge them.

Let me give just two examples of how games shape ecological perception and possibility. Firstly, my chapter on entropy takes as its major case study the genre (if it can be called that) of farm or agriculture games, popularized by Zynga’s FarmVille in the late 2000s. My critique of this neo-pastoral mode centered on its obscuring of human and nonhuman labor and grew directly out of work that received ASLE’s graduate student scholarly paper award in 2011, subsequently published in ISLE. (I have always treasured this early affirmation of what at the time seemed like a quirky side gig; ASLE makes a difference!). And secondly, last year, in pre-COVID times, I participated on a panel of parents for Career Day at my son’s elementary school. To explain what it is I do, I asked my audience of 4th-6th graders, first, whether they played games (a resounding yes!), second, if there was “nature” in the games they played (still mostly yes!), and then, finally, what they were typically doing to it while playing (destroying it! blasting it! blowing it up!). I rest my case.

While many see Playing Nature as a media/game studies book, because it is, after all, primarily about digital games, in truth it is equally if not more so an outgrowth of my longstanding interests in biology, literature, and film. Although I discuss many computer and video games, readers who make their patient way through the book will see that I also talk about games played in museums, outdoors, on walks, and gathered around a table (one of my favorite card games, Morels, simulates mushroom hunting while on a walk in the woods). My work joins other currents in game studies seeking to widen the ambit of current theories and methods, in this instance to include ecocritical and critical infrastructural analysis, while also taking part in the now decades-long trend toward greater inclusivity in the materials we look at as environmental scholars.

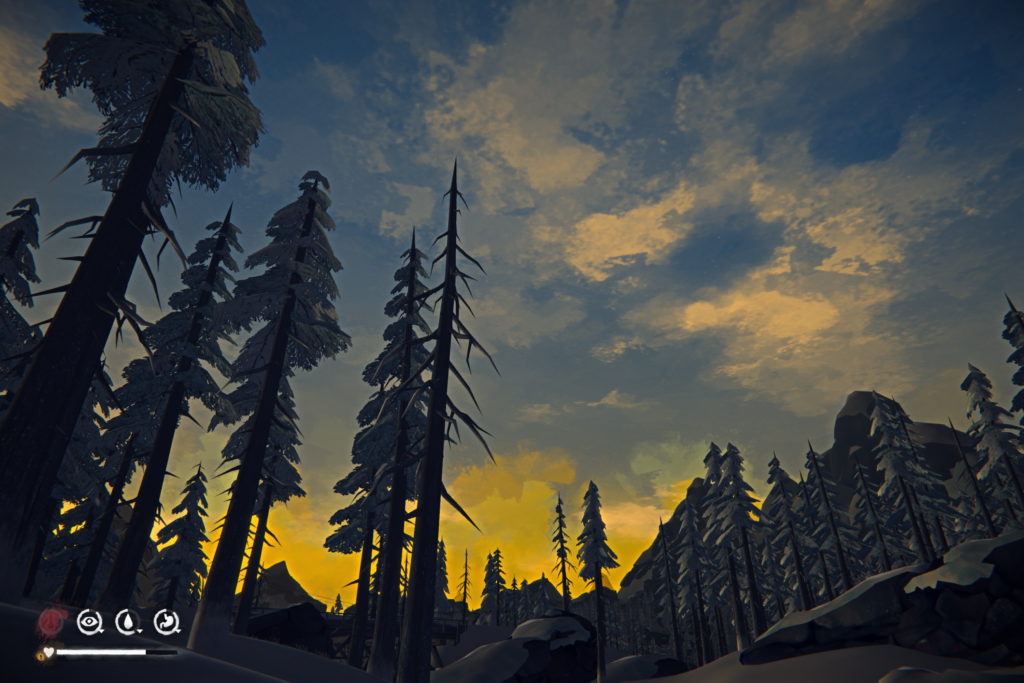

Does this mean you have to play games, or teach them, if you’re not already interested in them? Not necessarily, although I would argue that it is becoming harder and harder to ignore games’ broad cultural and material impacts. Instead, think of games as a way to meet your students where they already are. Back in 2008, the Pew Internet and American Life survey already concluded that games were “pervasive” in the lives of young adults: “Fully 97% of teens ages 12-17 play computer, web, portable, or console games.” When asked, by phone, half responded that they had played a game the day before. Put plainly, games might be a potent extension of your pedagogical toolkit. Since I cut my proverbial teeth on Shakespeare, creative nonfiction, classical rhetoric, 16mm film, BASIC, and early web design, I like to think I have a fairly catholic take on research and teaching materials. I may not teach novels these days, but I still love to assign the occasional short story or poem. There’s satisfaction in seeing your students reach the bleak end of Jack London’s “To Build a Fire.” But how would that compare to playing a survival game like Hinterland Studio’s The Long Dark, where you try to survive in the frozen Canadian wilderness following a plane crash and unspecified “geomagnetic disaster”? Or, how might reading Melody Jue’s fluidly disorienting Wild Blue Media alongside a playthrough of E-Line Media’s Beyond Blue generate productive resonance or friction?

An image of the natural world from The Long Dark.

Wonder arguably drives both scientific and playful attitudes to the world—as I like to say, game play and scientific work are not too distant cousins. However, play, like science, is not immune to the political. The much debunked “magic circle” of play (a term from Johan Huizinga) is instructively permeable to the real world. Take global warming’s threats to coastal golf courses and winter sports. Or the increasing attempts to think through collective action problems and climate denial or apathy using games. In fact, I think one of the reasons I find Greta Thunberg and the school strike for climate (skolstrejk för klimatet) movement so moving is because of their refusal of play. Their insistence that things cannot go on as they normally would includes a wrenching abdication of the carelessness and playfulness we once took for granted as part of childhood.

Meanwhile, the United Nations has fostered an alliance of game industry companies committed to various green “nudges” in the Playing for the Planet initiative. Some predict there will be 3 billion gamers by 2023, and alternate-reality game designer Jane McGonigal has estimated that we collectively spend 3 billion hours a week playing games. These numbers, and nudges, are in desperate need of contextualization – through participation, play, critique, collaboration, and research – and I genuinely look forward to the work that will contest and expand my own partial perspectives in Playing Nature.

Alenda Y. Chang is an Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (University of Minnesota Press, December 2019) and has recently published work in Resilience, Art Journal, electronic book review, and Feminist Media Histories. At UC Santa Barbara, Chang co-directs Wireframe, a research and teaching studio that promotes collaborative theoretical and creative media practice with investments in global social and environmental justice. She is also a founding co-editor of the new UC Press open-access journal, Media+Environment.

Alenda Y. Chang is an Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She is the author of Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games (University of Minnesota Press, December 2019) and has recently published work in Resilience, Art Journal, electronic book review, and Feminist Media Histories. At UC Santa Barbara, Chang co-directs Wireframe, a research and teaching studio that promotes collaborative theoretical and creative media practice with investments in global social and environmental justice. She is also a founding co-editor of the new UC Press open-access journal, Media+Environment.