This is Part I of a series on teaching ecohorror curated and introduced by Christy Tidwell.

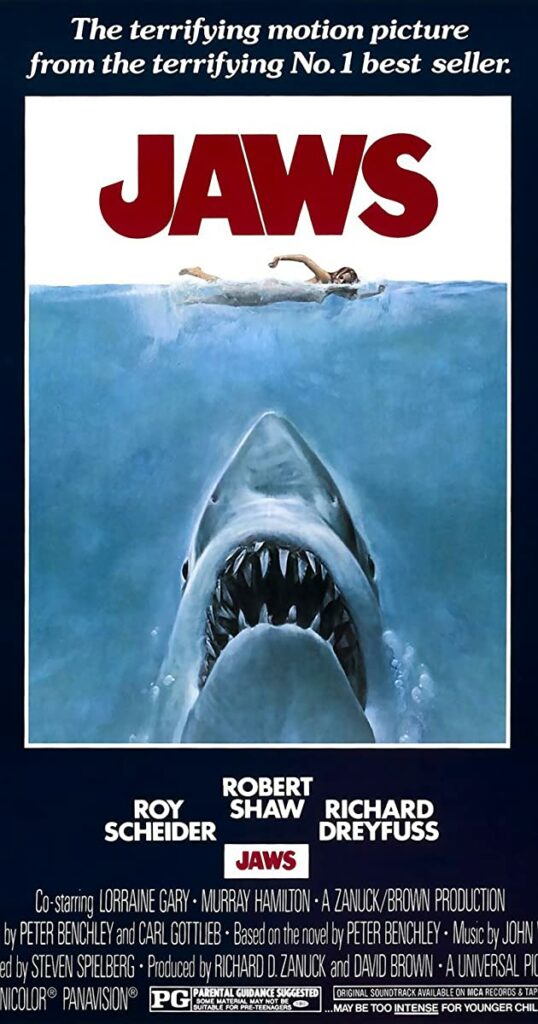

When people think of ecohorror, broadly defined as representing fears related to the natural world and/or the nonhuman, they often first think of nature-strikes-back narratives like The Birds (1963, dir. Alfred Hitchcock), Jaws (1975, dir. Steven Spielberg), The Day After Tomorrow (2004, dir. Roland Emmerich), or The Happening (2008, dir. M. Night Shyamalan). Jaws is perhaps the best-known and most influential example, a classic of ecohorror in which the natural world – in the form of the great white shark – is the enemy, opaque to our understanding and monstrous. (Importantly, human action also helps create the problem, but the memorable monster, the movie’s namesake, is the shark.)

When people think of ecohorror, broadly defined as representing fears related to the natural world and/or the nonhuman, they often first think of nature-strikes-back narratives like The Birds (1963, dir. Alfred Hitchcock), Jaws (1975, dir. Steven Spielberg), The Day After Tomorrow (2004, dir. Roland Emmerich), or The Happening (2008, dir. M. Night Shyamalan). Jaws is perhaps the best-known and most influential example, a classic of ecohorror in which the natural world – in the form of the great white shark – is the enemy, opaque to our understanding and monstrous. (Importantly, human action also helps create the problem, but the memorable monster, the movie’s namesake, is the shark.)

Jaws also points to creatures as another likely starting point for discussions of ecohorror, although ecohorror creatures may not always be monstrous animals (like the shark of Jaws and its many descendants on film). They could also be evolutionary holdovers and/or returns or genetically engineered hybrids as in the films Bridgitte Barclay and Katrina Maggiulli write about here: Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954, dir. Jack Arnold) and Splice (2009, dir. Vincenzo Natali). They address questions like these: How do movies about creatures (whether “natural” or human-made) shape our ideas about the relationship between human and nonhuman? What role does sympathy for the monster play in the films and students’ reactions to them? How do science and nature intersect in these films and in our reactions to the nonhuman?

The goal of this series is to highlight the thought and pedagogy of just a few of the many scholars working with ecohorror now. Each entry will include insights from 2-3 members of this ecohorror community, and several of the scholars and teachers included here are also contributors to the new edited collection Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene (edited by myself and Carter Soles). In Fear and Nature, we argue that ecohorror is an important way of understanding our contemporary environmental context, therefore making it a topic to consider for teaching students about environmental issues and attitudes; the book as a whole also contends that ecohorror is more wide-ranging (and politically diverse) than nature-strikes-back narratives, and the texts included in this teaching ecohorror series as whole reinforce that perspective.

Teaching Creature from the Black Lagoon – Bridgitte Barclay

Bridgitte Barclay is Associate Professor of English and Environmental Studies at Aurora University and is co-editor of Gender and Environment in Science Fiction.

One of my favorite ecohorror films to teach is Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), a beautiful classic creature feature that emphasizes evolution and extinction fears. I most recently used the film in a first-year seminar course, Speculative Fiction and Film, placing it between the AI thriller Ex Machina (2014) and Maria Dahvana Headley’s Beowulf-inspired The Mere Wife (2018) as we explored the boundaries of “human.” Creature from the Black Lagoon reflects similar fears with its destabilization of human exceptionalism through evolutionary narratives as well as midcentury extinction fears after notable species loss and the extinction potential of atomic warfare.

Two scenes demonstrate those fears especially well. The first is the beginning of the film, with the opening voiceover narrating as Big Bang visuals play. The narrator says, “In infinite variety, living things appear, and change, and reach the land… leaving a record of their coming of their struggle to survive, and of their eventual end” as a creature emerges from the ocean and walks on land. This moves immediately into images of a petrified creature hand sticking out from the rocks, allowing us to explore Anthopocenic narratives of “the record of life […] written on the land.” As part of what I call the de-extinction subgenre of environmental creature features, the film’s opening scene exposes cultural fears about defining human, blurring human-nonhuman boundaries, and species extinctions.

The second scene that is useful in teaching ecohorror is the famous underwater scene with Creature mirroring Kay swimming, a scene which both horrifies and establishes empathy for Creature by shifting perspectives and prodding the boundary between otherness and relatedness. The camera angle is largely the Creature’s POV, looking up as Kay swims on the water’s surface, making Kay the “other.” But, when the POV shifts and Creature and Kay are framed together, viewers see their similar silhouettes and movements. Such a scene not only scares those of us who may always be expecting something terrible to drag us under from below the water’s surface (I still blame the opening scene of Jaws (1975) for this, a scene that echoes this one in Creature), but it also establishes commonality among species with the mirrored movements.

Students always appreciate Creature’s beauty and genre conventions, but even more interestingly, I have been surprised by the complex discussions we have about monstrosity. When I last taught it, some students empathized with Creature and were appalled at the scientists’ invasion and pollution of the Black Lagoon. Other students found Creature violent and sided with the scientists, which surprised me. They noted that he killed first and his presumably sexual aggression against Kay. The complicated entanglement of not only the scientists’ pollution of the lagoon’s ecosystem and aggression against the Creature but also the Creature’s sexual aggression and murder of Indigenous characters make for fantastic ecohorror discussions.

Teaching Splice – Katrina Maggiulli

Katrina Maggiulli is a PhD candidate and instructor in Environmental Sciences, Studies & Policy and English at the University of Oregon, located on Kalapuya ilihi, the traditional indigenous homeland of the Kalapuya people. Her work broadly spans ethical engagements with other species in conservation policy, practice, education, and imaginaries.

Canadian director and writer Vincenzo Natali’s 2009 film Splice has long been one of my favorite ecohorror works to think and teach with. The biotech monster movie follows the story of the scientist-power-couple Clive (Adrien Brody) and Elsa (Sarah Polley) as they go behind their pharmaceutical company employer’s back to splice together human and nonhuman genes and create Dren (Delphine Chanéac). Dren begins as a specimen but becomes a daughter, a lover, and a killer in this twisted story that blends the laboratory with the domestic.

I love this film because it doesn’t fail to make you uncomfortable in some way – it is hard to feel indifferent towards it, which provokes heated discussion in the classroom. To begin a class on Splice, I like to ask my students to offer one word to describe their emotional response to the movie; “disturbed,” “disgusted,” and “grossed out” all regularly appear in such a discussion. These offer the class compelling places to begin: what is it that so unsettles about the figure of Dren and her complex relationship with her creators? Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s foundational piece “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” (1996) offers useful entry points into such a question: what cultural moments, preoccupations, or taboos does Dren embody? What categories are in crisis in this film? Dren is a quintessential monster figure; she gleefully flouts all binaries and blends identities, species, and sexes in one body.

But what I see as the most compelling part of the film is that she might be the least “monstrous” of the lead characters. We watch Clive and Elsa commit numerous atrocities over the course of the film, all culminating in an awkward (and chilling) scene in Clive and Elsa’s apartment where the couple eventually decides they must “end” the experiment. This sets up a provocative question for a class: who is the monster in this monster movie? Dren is not the only “boundary crosser” in this film, and the mixed identities of parents, scientists, and lovers that Clive and Elsa carry also renders them complicated category-flouting figures. This categorical confusion is underscored by Clive’s lament that “We crossed a line. Things got confused” – what was morally acceptable became muddled for Clive and Elsa after they breached the human-nonhuman boundary.

Color in the film is one way these boundaries are depicted—the home and the domestic feature warm browns and golds, the laboratory is a cold blue and silver. Analyzing the moments where these colors mingle on-screen (the scenes where Elsa cuts off Dren’s stinger or when Clive monitors Dren on the computer are both perfect examples) can help students unpack the complications of boundary crossing in the film using the aesthetics of the film itself.

Splice offers a number of productive topics for an ecohorror course – themes of biotechnology and bioethics, the human-nonhuman binary, concepts of the natural and unnatural, the relationship between living organisms and capital, and more. It is important to note, however, that the film culminates with Dren changing sex (to male) and sexually assaulting Elsa (which results in Elsa’s pregnancy). A discussion on troubling a common and highly problematic rendering of trans people as “monstrous” should therefore be on your radar if you are interested in teaching with this film.