By Cajetan Iheka

“Why can’t we be seen?” asks Kenyan farmer and activist Kisulu Musya when he appears with his family in Julia Dahr’s climate change film Thank You For the Rain (2017). I discuss the film in the second chapter of my new book African Ecomedia: Network Forms, Planetary Politics. In the pervading darkness, the camera cannot quite capture Kisulu’s family until daylight intervenes. Kisulu’s words bespeak infrastructural lack and uneven development – they are the expression of a desire to be legible, visible, as political agents – but his question can also be interpreted as a critique of the camera’s bias against Black skin. Kisulu’s words take on further significance as the film turns to document his participation in the United Nations Conference on Climate Change (COP 21). Kisilu attends the Paris conference with anticipation of a favorable outcome for poor communities like his own. In Paris, he hopes to find a platform from which they might be seen and heard. Although communities like Kisilu’s contribute little to climate change, they are already disproportionately burdened with its extreme consequences including drought and flooding that threaten agriculture and their livelihood. Ultimately, a deal is reached in Paris, but it falls short of the ambitious proposals crucial for stemming climate change. Kisilu’s experience in Paris is not altogether different from that of Naomi Klein at the United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen in 2009, where world leaders failed to reach a significant deal. Her realization then “that no one was coming to save us” is useful for apprehending Kisilu’s frustration at the end of the Paris meeting almost a decade later (Klein 12).

Writing this piece as COP26 gets underway in Glasgow, Scotland, the largest carbon emitters are yet to significantly cut their pollution while communities in Africa (like Kisulu’s) increasingly directly suffer the impact of climate change. African communities also suffer from the extraction of minerals and other resources that power the world. For example, the continent is where our media technologies derive essential components such as oil and coltan and where some discarded gadgets return for recycling through unsafe practices. Africa continues to suffer the invisibility that Kisulu’s lament pinpoints. This is evident, for instance, in the Associated Press’s decision to crop the young Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate out of a picture with Greta Thunberg and other activists at the 2020 World Economic Forum.

My new book takes Kisulu’s question, why can’t we be seen, as its animating impulse. It does this by foregrounding representations of environmental violence and extractive practices in African visual culture: namely, mineral mining, electronic recycling, commercial agriculture, and “trophy” hunting. As I write in the introduction, “Africa is the other repressed and invisible factor in the operations of media infrastructure as the continent remains at the margins of intellectual discussions and geopolitics despite its major contribution to global modernity and the supply chain. In foregrounding the continent and a visual archive, I intend to account for the socioecological costs of media processes and unearth what happens behind the scene of a global supply chain” (6). Kisulu’s grammar of visibility and the insights afforded by the work of other artists discussed in the book allow me to position Africans as not mere victims of ecological devastation but more importantly as knowledge producers – as a people actively working to counteract the effects of globalization in their communities.

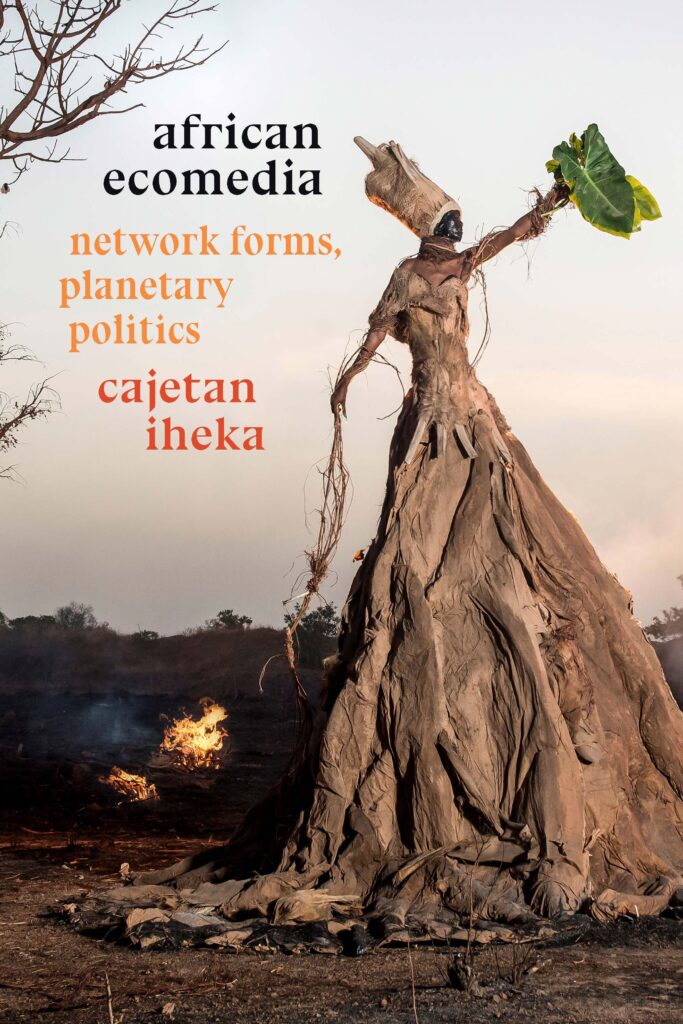

Film and photography constitute the bulk of my archive, but I also examine sculpture, video art, and futuristic artistic installations. In addition to Thank You For the Rain, for instance, I analyze “Sarogua Mourning” (2011), a video artwork by Zina Saro-Wawa, daughter of Nigeria’s environmental martyr Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was killed by the Nigerian government for his activism against the despoliation of the Niger Delta from oil exploration. The younger Saro-Wiwa’s work centers a decolonial place-based performance as a crucial response to ecotrauma emerging from oil culture. Fabrice Monteiro’s Prophecy (2015), a series of captivating photographs of figures clothed in trash in Senegal, offer a compelling venue for discussing waste aesthetics and the project of futurity in the first chapter, while the urban imaginaries of Guy Tillim’s photographs of Johannesburg inner cities (2005) and Olalekan Jeyifous’ futuristic renderings of Lagos in Shanty Megastructures (2015) make possible the envisioning of the ecological city to come (see Chapter Five). To align methodological approaches with the complex demands of ecology as both an intellectual and socio-political project, I have opted for media relationality over medium specificity in conceptualizing this book. Consequently, African Ecomedia offers a model for an ecological media studies for the twenty-first century, one encompassing “media arts including film and photography as well as resource media such as oil and uranium alongside their impacts on and implications for elemental media (fire, air, water, earth)” (8).

Olalekan Jeyifous, Shanty Megastructures (2015)

How do we secure the earth – our common home – for the future? How can the environmental humanities and media studies best tackle the project of planetary futures? My book positions Africa as ground zero for these critical projects of field revitalization and world reconstitution. I locate a worldmaking ethos in the afforestation program that Kisulu spearheads in Thank You For the Rain and in the fair-trade relationship between Cameroon banana farmers and their collaborators in the United States in Franck Bieleu’s film The Big Banana (2011). I describe a related ethos in the recuperative aesthetics discussed in the first chapter and in Afrofuturistic projects such as Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018) and Wanuri Kahiu’s Pumzi (2009).

The redemption of Blackness as site of beauty and creativity is a shared feature of the aesthetic works I analyze, and it is an important practice within the climate of a durable anti-Blackness. However, African Ecomedia warns for vigilance so that the future we imagine does not retain the violence of the present. We must especially be careful about the kinds of “slow violence” that Rob Nixon identifies, those that happen out of sight, as we design and implement alternative possibilities in speculative media. Ultimately, it is not enough to scrutinize the content of media. Media production, distribution, and consumption as well as recycling practices would have to be reworked to meet the demand of a decarbonized or extremely low-carbon future. In place of the media of excess saturating contemporary life, it is time to embrace what I call an “imperfect media,” that is, a media of scarcity. I argue in the book’s epilogue that we can look to African media practices for “the creative, improvisational, and experimental impulses that scarcity engenders” (224).

Cajetan Iheka is Associate Professor of English at Yale University. He is the author of Naturalizing Africa: Ecological Violence, Agency, and Postcolonial Resistance in African Literature (Cambridge University Press, 2018), winner of the 2019 Ecocriticism Book Award of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment, and the 2020 First Book Prize of the African Literature Association. His new monograph, African Ecomedia: Network Forms, Planetary Politics, was published by Duke University Press in Fall 2021. He is also editor of the MLA volume Teaching Postcolonial Environmental Literature and Media (2022).