This is the second part of a series on teaching ecohorror curated and introduced by Christy Tidwell. (Read Part 1 here.)

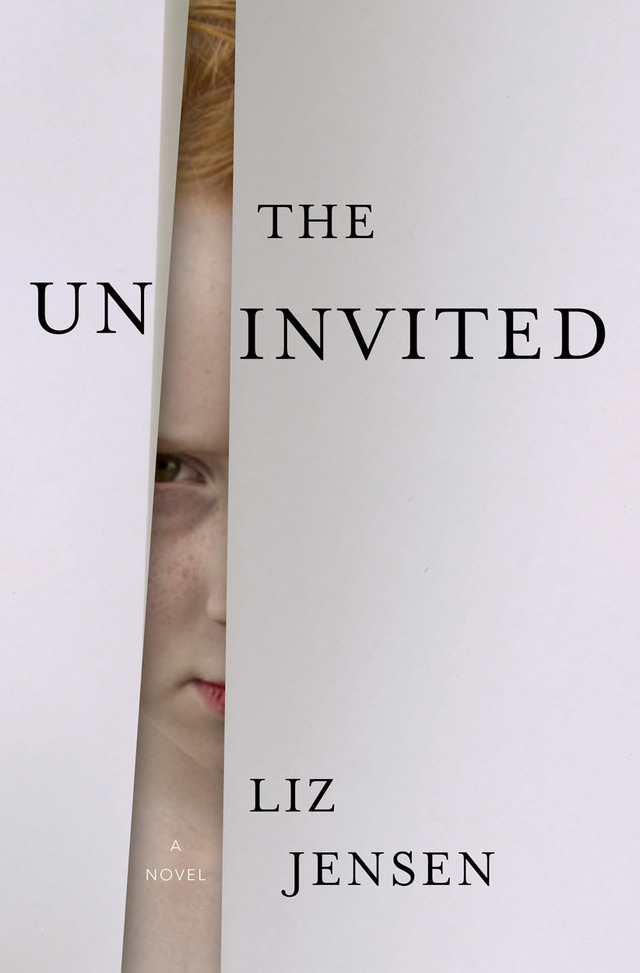

The two texts discussed by Ashley Kniss and Bernice Murphy in this post illustrate that ecohorror covers much more than creatures or nature-strikes-back narratives. Ecohorror, as Stephen Rust and Carter Soles write, “assumes that environmental disruption is haunting humanity’s relationship to the non-human world,” and Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014) and Liz Jensen’s The Uninvited (2012) illustrate this haunting in fascinating ways. Both novels, as Kniss and Murphy point out, ask readers and students to think about big-picture issues (e.g., climate change) and collective responses to the world as opposed to merely individual ones.

The two texts discussed by Ashley Kniss and Bernice Murphy in this post illustrate that ecohorror covers much more than creatures or nature-strikes-back narratives. Ecohorror, as Stephen Rust and Carter Soles write, “assumes that environmental disruption is haunting humanity’s relationship to the non-human world,” and Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014) and Liz Jensen’s The Uninvited (2012) illustrate this haunting in fascinating ways. Both novels, as Kniss and Murphy point out, ask readers and students to think about big-picture issues (e.g., climate change) and collective responses to the world as opposed to merely individual ones.

In doing so, these texts reveal the wider range of possibilities offered by ecohorror. Ecohorror can emphasize nature’s threat to the individual or personal fears of the natural world (animal attack narratives are often focused narrowly on an individual, for instance), but it can also narrativize global threats to humanity as a species or to the planet as a whole. Some ecohorror combines these two effects. Crawl (2019, dir. Alexandre Aja), for instance, is an animal horror film, but it is also a climate change film. It is about one woman fighting off alligators as well the larger threat of climate change, since climate change is what creates the storm that frees the alligators and traps her with them. These fears are combined in the movie and, as I have argued in a piece for Horror Homeroom, the film even (likely inadvertently) points to another possibility for ecohorror, which is to serve as a reminder that humans aren’t so special.

Some ecohorror – as Kniss and Murphy indicate here – asks us to consider whether the changes that are so easily seen as threatening are in fact all bad and to consider the perspective of the nonhuman. This can be unnerving or destabilizing, a common effect of horror, but it can also be illuminating.

Teaching Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation – Ashley Kniss

Ashley Kniss is a Senior Lecturer at Stevenson University.

One of the prominent themes in ecohorror texts is the utter indifference of the eco-other to humankind. In ecohorror, human life means very little to a hungry shark, flesh-eating isopod, carnivorous plant, or natural disaster. The nonhuman others in ecohorror are almost always monsters, and, as such, how do we convince students to acknowledge the importance of something that refuses to be anthropomorphized, that remains disturbingly and indifferently alien? I love teaching Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation (2014) for this very reason. The monster in the novel is a cordoned-off section of wilderness called Area X that has experienced an “event.” While there are many mysteries about Area X, we know that it did contain humans. Now, however, the inhabitants are limited to mutant creatures that bear strange likenesses to humans and moss “eruptions” in human form. What’s more, Area X is newly pristine and without the pollutants that mar so much of the planet, and it is growing, subsuming human structures and humankind as it expands.

The narrator, a hyper-objective scientist, known only as “the biologist,” provides students with a glimpse of how we might learn to care about the alien, indifferent aspects of nature, even as we acknowledge the horror inherent in these features as well. My students never like the biologist at first because she seems cold and inhuman. In fact, in my notes from class, I recorded one student who called her “creepy” and “sterile.” However, in her contribution to a roundtable discussion of Annihilation in Gothic Nature, Sara Crosby describes her as having an “adaptive, post-human neuroatypicality, which impels her to identify more strongly with ecosystems than with human individuals.” This is something I try to nudge my students to recognize. Once students begin to identify the biologist’s love for nonhuman ecosystems, they begin to think about animal and plant intelligence in nuanced ways, seeing (bio)logical processes and behaviors in nature that may be alien to human logic but make perfect sense in a biological setting, especially one like Area X.

Thinking in terms of ecosystems rather than individuals is often novel to students, but the biologist shows us the way. She avoids the human proclivity to focus on the individual rather than the collective. My students struggle with VanderMeer’s implied solution to the problems of the Anthropocene – transformation, mutation, a loss of human identity as it is subsumed into a collective ecological identity that blends and levels the human and nonhuman. If I’m being honest, I struggle with this too. However, one passage that resonates with students is the biologist’s reflection at the end of the novel: “The terrible thing, the thought I cannot dislodge after all I have seen, is that I can no longer say with conviction that this is a bad thing. Not when looking at the pristine nature of Area X and then the world beyond, which we have altered so much” (192). Some students are quick to agree with the biologist while other students are thoroughly disturbed by the biologist’s suggestion. Either way, Annihilation teaches students to consider ecosystems as a whole, to think about the relationships between human and nonhuman in new ways, and, at the very least, to acknowledge other(ed) ways and forms of being in the world outside of the human.

Teaching Liz Jensen’s The Uninvited – Bernice Murphy

Bernice M. Murphy is Associate Professor/Lecturer in Popular Literature at the School of English, Trinity College, Dublin.

Twitter: @MurphGothic

I regularly assign Liz Jensen’s 2012 novel The Uninvited in my “Modern Horror Fiction” module, which is taught to undergraduate students in their third and fourth years. Students taking the course tend to fall into two categories: there are those who are already horror fans, and, as such, have some knowledge of the genre, and those who find horror terrifying but fascinating. I always devote a week to ecohorror, using the first half of that class to survey the sub-genre’s evolution since the 1950s. We discuss Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) before I provide an overview of the animal-focused ‘Nature Strikes Back’ movies and novels which followed in the wake of The Birds (1963).

I regularly assign Liz Jensen’s 2012 novel The Uninvited in my “Modern Horror Fiction” module, which is taught to undergraduate students in their third and fourth years. Students taking the course tend to fall into two categories: there are those who are already horror fans, and, as such, have some knowledge of the genre, and those who find horror terrifying but fascinating. I always devote a week to ecohorror, using the first half of that class to survey the sub-genre’s evolution since the 1950s. We discuss Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) before I provide an overview of the animal-focused ‘Nature Strikes Back’ movies and novels which followed in the wake of The Birds (1963).

I use The Uninvited as a primary text because it advances the ethical and thematic concerns raised by my introductory century survey of the topic. In particular, it facilitates discussion of the most pressing ecological crisis of our time: climate change, and the ways in which it is already transforming our lives and our futures.

The novel begins with a conceit which will be familiar to anyone who has ever read Stephen King’s “Children of the Corn” (1977). For no apparent reason, youngsters all over the world begin to violently attack adults and regress into a primitive state. However, as Jensen’s protagonist Hesketh Lock investigates several of these cases (he’s a trouble-shooting corporate anthropologist), it soon becomes clear that this is not yet another ‘evil child’ narrative. It is rather an ambitious and original ecohorror novel in which the horrific violence enacted by those who will be most impacted by the societal and environmental ravages of climate change – the next generation – is much more than simple “acting out” or revenge against the adult world. It is rather an extreme – but understandable – survival strategy.

As the plot unfolds and what at first seems like a random spate of horrific crimes becomes a global crisis, Hesketh’s desire to figure things out is increased by his desire to protect Freddie, the son of his former partner, who is beginning to exhibit many of the same symptoms as the other children stricken with this mysterious affliction. The physical and psychological transformations undergone by Freddie and cohort leave us in little doubt that in the near future, if things continue as they have done, the entire planet will be a toxic dystopian landscape, populated only by a few doomed and feral survivors who must eat human flesh in order to survive.

The Uninvited tends to evoke strong reactions: students generally either love it or are angered by it. The ending – which is both bleak and tentatively hopeful – lends itself towards considerations of the ways in which the “End of Nature” theorized by Bill McKibben will require us to comprehensively rethink our relationship with the world around us and our place in it as a species. As we are told of the world’s children late in the novel, by which time they simultaneously inhabit both the grim present and even the more dystopian (possible) future: “They came as saviours, bearing the undeserved and astonishing gift of a second chance. And it was thanks to them that we discovered a new metaphysics of being.”