By Jessica Hurley

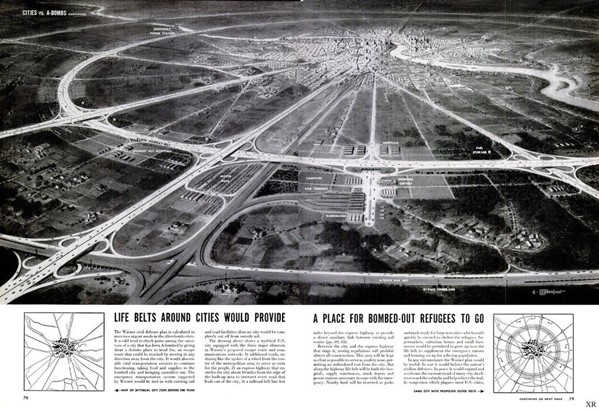

Infrastructures of Apocalypse offers the first account within literary studies of nuclearization in the United States that focuses not on the imagined Third World War to come but on the infrastructural, environmental, and socio-political transformations of the U.S. that have resulted from the nation’s commitment to nuclear technology. Nuclearization has radically transformed the environmental realities of American life, from the suburbs and highway systems that were built to facilitate civil defense to the infrastructures of nuclear power that constitute some of the most polluted sites on the planet. And yet this transformation remains shielded by what Michelle Murphy calls a regime of imperceptibility, a carefully constructed invisibility that prevents us from knowing what we’re looking at as we’re looking at it. With this book, I hope to break through some of the regime of imperceptibility that surrounds the nuclear complex and help readers to apprehend how nuclearization is embedded in our environments.

Life, “How U.S. Cities Can Prepare for Atomic War,” December 18, 1950. https://www.loc.gov/item/2012648247/.

This ecocritical approach to the nuclear age raises a broader question: what does it mean to live in a world that is infrastructured to produce apocalypse? This question has resonances far beyond nuclearization; climate change, genocide, mass extinction, and the COVID-19 pandemic are all apocalyptic consequences of what Winona LaDuke and Deborah Cowen have named “Wiindigo infrastructure,” ecocidal settler-colonial infrastructures that disposition the world towards its own destruction. In this sense, infrastructure produces the apocalypse narratives that we live every day.

And yet as a literature scholar I’m interested, too, in how apocalypse narratives themselves shape the emergence of new infrastructures – in this case, the infrastructures of nuclearization. As my research shows, different kinds of apocalypse narratives have been foundational to decisions about what nuclear infrastructures would be built and where, from the mid-century resurgence of the millennial image of the U.S. as the “city on a hill” that undergirds suburbanization to Reagan’s determination to bring about the end of history with the Strategic Defense Initiative. At the same time, these new nuclear apocalypse narratives are shaped by older stories about futurelessness that is unevenly distributed along the lines of race, indigeneity, class, gender, sexuality, and disability. According to Western chronopolitics from 1492 onwards (and intensified in Enlightenment thought), whiteness is marked by its access to futurity while it defines other social forms through their futurelessness: race as backwards, queerness as sterile, indigeneity as vanishing, disability as an unimaginable part of any desirable future, and so on. What we see in the narrative-material construction of nuclear infrastructures is how beliefs about the inherent futurelessness of social groups come to shape the inequitable exposure to harm that these infrastructures produce; in civil defense’s reorganization of the urban environment, for instance, the valued white citizenry is moved to the suburbs, but the Black population, already seen as futureless from Kant and Hegel onwards, is left behind in the city as the disposable atomic target. As I write in the book’s introduction, “the narrative form of apocalypse motivates the reshaping of the environment while the structural form of racial hierarchy shapes the environment that will be produced; apocalypse gets the suburb built, but anti-Blackness determines who will live there” (13).

It is here that the book’s larger intervention into how we interpret the chronopolitics of apocalypse emerges. Apocalypse is frightening because it threatens the future, but what if you’ve always been positioned by the dominant culture as inherently futureless? Does futurelessness look different if your own access to the future has long been sacrificed to ensure the continuity of the social order? If the future doesn’t have you in it – Black, queer, Native, crip – then how much do you really want it, anyway?

It is here that the book’s larger intervention into how we interpret the chronopolitics of apocalypse emerges. Apocalypse is frightening because it threatens the future, but what if you’ve always been positioned by the dominant culture as inherently futureless? Does futurelessness look different if your own access to the future has long been sacrificed to ensure the continuity of the social order? If the future doesn’t have you in it – Black, queer, Native, crip – then how much do you really want it, anyway?

The question that this book addresses is fundamentally about the political potential of futurelessness and of apocalypse as a narrative form: what does apocalypse, as a form for shaping our lived experience, do for people whose futures are already foreclosed by nuclear infrastructures – infrastructures that are themselves manifestations of much older systems of power that distribute futurity inequitably? I found answers to this question in the writings of Toni Cade Bambara, James Baldwin, Samuel R. Delany, Tony Kushner, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Ruth Ozeki, writers who consider nuclear infrastructures within these longer settler-capitalist histories. In these works, I found an apocalypticism that wasn’t always immediately recognizable as such – none of them represent traditional nuclear apocalypse scenarios – but that was defined, rather, by a present that was shaped by nuclear infrastructures and oriented towards a radical futurelessness. These works entrain the reader to inhabit a world without a future. They shook me; I was not the same after reading them as I was before. Infrastructures of Apocalypse is an attempt to understand how these works of narrative fiction could so radically change my lived experience, my apprehension of time and space, through their narrative construction of a futureless present as a demand for justice in the nuclear age.

This futureless present offers a different orientation for political and social struggle. In the futureless present, politics might be oriented towards impossible futures: futures that we can’t yet imagine, or futures that seem literally impossible from where we are right now. Without a future we cannot be motivated by hope or by a set of plausible outcomes, but we might be left instead with something like ethics: we fight not because we believe that we will be successful, but because it is the right thing to do. When we turn our focus away from organizing towards what seems possible to achieve in the future, other orientations become possible: an ethical orientation, for instance, in which we fight for abolition not because it seems plausible but because white supremacist police brutality is profoundly wrong.

As a teacher, I find that my work resonates with students in a number of ways. I teach in Northern Virginia, about 20 miles from Washington, D.C., and my students are always shocked to learn about how our everyday lives – everything from the demographic makeup of our neighborhoods to the traffic that we sit in every day – are profoundly shaped by the nuclear logics that find material form in our built and natural environments. For instructors teaching this book, having students conduct small research projects on how their neighborhoods have been shaped by militarization (especially within what Catherine Lutz has called the “nuclear mode of warfare”) is a profound experience for them, as they come to see how environments that we generally think of having nothing to do with the violence of war are in fact legacy systems of world-killing technologies. Reading for what I call “the nuclear mundane” also opens up a new dimension to a lot of twentieth- and twenty-first century literature, while the book’s attentiveness to how narratives about race, indigeneity and sexuality get built into the environment make it a productive reading for classes about environmental justice across a number of disciplinary perspectives.

I’ve also worked with students on using futurelessness to disrupt our sense of what’s possible. In one of my favorite teaching experiences, I led a workshop at the College of Wooster where students began by writing lists of impossible futures: things that they wanted but thought would never happen. They then worked in groups to make one of those things happen; over the course of an hour, students actualized everything from “I want to see in black and white” to “I want to go to the grocery store without the security guard following me around.” Students then went back to their lists and wrote a present-tense description of themselves experiencing one of their impossible futures. Their responses were beautiful and profoundly moving, and what can be a fairly dry narratological argument about the relationship between narrative time and the imagination came alive in powerful and unexpected ways. The question of how we live in an apocalyptically infrastructured world is a fundamentally phenomenological one, and approaches to teaching with the book that ask students to explore their own lived experiences have often produced the best results.

The futureless world is the one that we live in, inescapably if with unevenly distributed intensity. What this book offers is a way of thinking about how the work of liberation can continue when all avenues of progress appear to be foreclosed, when the world is infrastructured by and towards apocalypse. It is for everyone who wants to understand how we are infrastructured into futurelessness, and how we can go on fighting anyway. I hope you find it useful.

May 30, 2020, Minneapolis. Photo by Aren Aizura.

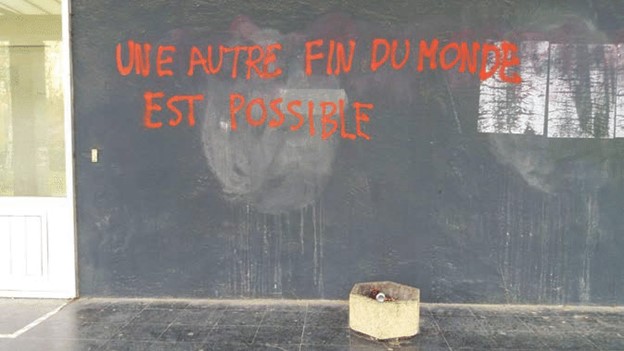

Une autre fin du monde est possible, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre. Photo courtesy of Audrey Bochaton.

Jessica Hurley is Assistant Professor of English at George Mason University. She is the author of Infrastructures of Apocalypse: American Literature and the Nuclear Complex (University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Her work has appeared in symplokē, Comparative Literature Studies, Commonwealth Essays and Studies, American Literature, Extrapolation, Frame, The Faulkner Journal, and the edited collection The Silence of Fallout: Nuclear Criticism in a Post-Cold War World, and it has been recognized by the Don D. Walker Prize in Western Literature, the 1921 Prize in American Literature, and the Jim Hinkle Memorial Prize. In 2018 she co-edited a special issue of ASAP/Journal titled Apocalypse.

Jessica Hurley is Assistant Professor of English at George Mason University. She is the author of Infrastructures of Apocalypse: American Literature and the Nuclear Complex (University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Her work has appeared in symplokē, Comparative Literature Studies, Commonwealth Essays and Studies, American Literature, Extrapolation, Frame, The Faulkner Journal, and the edited collection The Silence of Fallout: Nuclear Criticism in a Post-Cold War World, and it has been recognized by the Don D. Walker Prize in Western Literature, the 1921 Prize in American Literature, and the Jim Hinkle Memorial Prize. In 2018 she co-edited a special issue of ASAP/Journal titled Apocalypse.