The 2021 meeting of the Modern Language Association included two ASLE-sponsored sessions plus several other sessions addressing the environmental humanities and including ASLE members. In fact, this feature includes 10 reports from the conference – an embarrassment of riches! – including sessions on Romanticism, Depression-era literature, ecofascism, and infrastructure.

Comparative Environmentalisms

Report by Benjamin Mangrum, University of the South

Benjamin Mangrum, Presider

Participants: Carolina Diaz (California Institute of the Arts), Merve Tabur (Penn State University), Antoine Traisnel (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor)

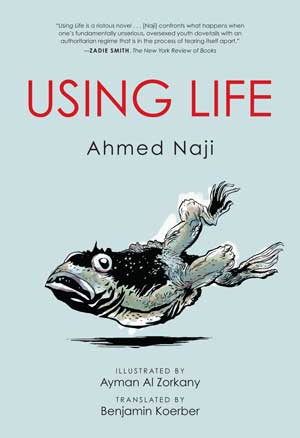

Comparative Environmentalisms featured presentations on literature, art, and plant theory. Carolina A. Díaz examined the feminist artist and activist Cecilia Vicuña, whose art installations often include the aesthetic element of a red yarn of wool. Díaz views this element as entangled with the politics of water in Chile and the history of the Pinochet dictatorship. According to Díaz, the red wool reveals how Vicuña counters ecological imperialism and the colonial objectification of nature. Merve Tabur examined the intersection of politics and environmentalism in contemporary Arabic fiction, focusing particularly on Ahmed Naji’s Using Life (2014), which led to the author’s imprisonment in Egypt because of its supposedly obscene material. Tabur interprets Naji’s book by adapting Nicole Seymour’s idea of “bad environmentalism.” Naji’s book uses absurdity and irony to question the greening of cityscapes and buildings in such metropolitan centers as Cairo. In contrast to the technologically sprouted greenery of contemporary urban development, Using Life represents environmentalism as an object of ridicule to show the links between “green” values and neoliberal development. Finally, Antoine Traisnel compares contemporary plant theory to Henry David Thoreau’s settler garden practices at Walden Pond. An offshoot of posthumanism, plant theory queries the negligence or indifference to the life of plants and imagines the mutual co-penetration of life forms. Traisnel uses Thoreau’s work to consider the promises and limitations of this theory. In particular, Thoreau’s work suggests how modern biopolitics does not spurn but actually incorporates plant life.

Comparative Environmentalisms featured presentations on literature, art, and plant theory. Carolina A. Díaz examined the feminist artist and activist Cecilia Vicuña, whose art installations often include the aesthetic element of a red yarn of wool. Díaz views this element as entangled with the politics of water in Chile and the history of the Pinochet dictatorship. According to Díaz, the red wool reveals how Vicuña counters ecological imperialism and the colonial objectification of nature. Merve Tabur examined the intersection of politics and environmentalism in contemporary Arabic fiction, focusing particularly on Ahmed Naji’s Using Life (2014), which led to the author’s imprisonment in Egypt because of its supposedly obscene material. Tabur interprets Naji’s book by adapting Nicole Seymour’s idea of “bad environmentalism.” Naji’s book uses absurdity and irony to question the greening of cityscapes and buildings in such metropolitan centers as Cairo. In contrast to the technologically sprouted greenery of contemporary urban development, Using Life represents environmentalism as an object of ridicule to show the links between “green” values and neoliberal development. Finally, Antoine Traisnel compares contemporary plant theory to Henry David Thoreau’s settler garden practices at Walden Pond. An offshoot of posthumanism, plant theory queries the negligence or indifference to the life of plants and imagines the mutual co-penetration of life forms. Traisnel uses Thoreau’s work to consider the promises and limitations of this theory. In particular, Thoreau’s work suggests how modern biopolitics does not spurn but actually incorporates plant life.

Depression-era Environmental Literature in the U.S.

Report by Matthew Lambert, Northwestern Oklahoma State University

Presider: Matthew Lambert

Participants: Matthew Lambert (Northwestern Oklahoma State University), Cassie Galentine (University of Oregon), Sheila Liming (Champlain College), and Douglas Dowland (Ohio Northern University)

Dust storm approaching Stratford, Texas. Dust bowl surveying in Texas. NOAA George E. Marsh Album.

Each of the four papers presented during the depression-era environmental literature panel at MLA 2021 focused on the often-overlooked importance of environmental thought and justice to writers from the late 1920s to the early 1940s. Matthew Lambert, author of the The Green Depression: American Ecoliterature in the 1930s and 40s (University Press of Mississippi, 2020) and organizer of the panel, presented first. His paper, “‘High Water Everywhere’: Flooding and Race in Hurston and Wright,” focused on ways that Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God and Richard Wright’s “Down by the Riverside” similarly depict the unique risks that African Americans faced during the major human-influenced flooding events of the late 1920s. Next, Cassie Galentine presented on the racializing function that dust and hygiene play for white migrant workers in California in her paper “‘We ain’t human, we’re figures on the books’: Multi-racial Labor Organizing in Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown.” Sheila Liming then drew connections between community building and land stewardship in her paper “We Have Always Been Depressed: Meridel Le Sueur, The Midwest, and Collective Agriculture.” Lastly, Douglas Dowland described ways that John Steinbeck and the biologist Ed Rickets used their specimen-collecting trip to the Gulf of California in 1940 to critique the environmental, social, and economic values of American individualism in his paper “Steinbeck, Ricketts, and the Politics of Friendship in The Sea of Cortez.” The papers led to a robust Q&A that continued after the panel ended. Questions focused on the relationship between the political and environmental affiliations of the authors, the role of the nonhuman in depression-era literature, the theory of friendship in Steinbeck and Ricketts’ book, and the publication history of Sanora Babb’s Whose Names are Unknown.

Environmental Media

Report by Alenda Chang, University of California, Santa Barbara, and Christina Gerhardt, University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa

Presiders: Alenda Chang (University of California, Santa Barbara), Christina Gerhardt (U of Hawai‘i, Mānoa)

Participants: Somak Mukherjee (University of California, Santa Barbara), Jeffrey Moro (University of Maryland, College Park), Nicholas Silcox (New York University), Jamie Jones (University of Illinois, Urbana)

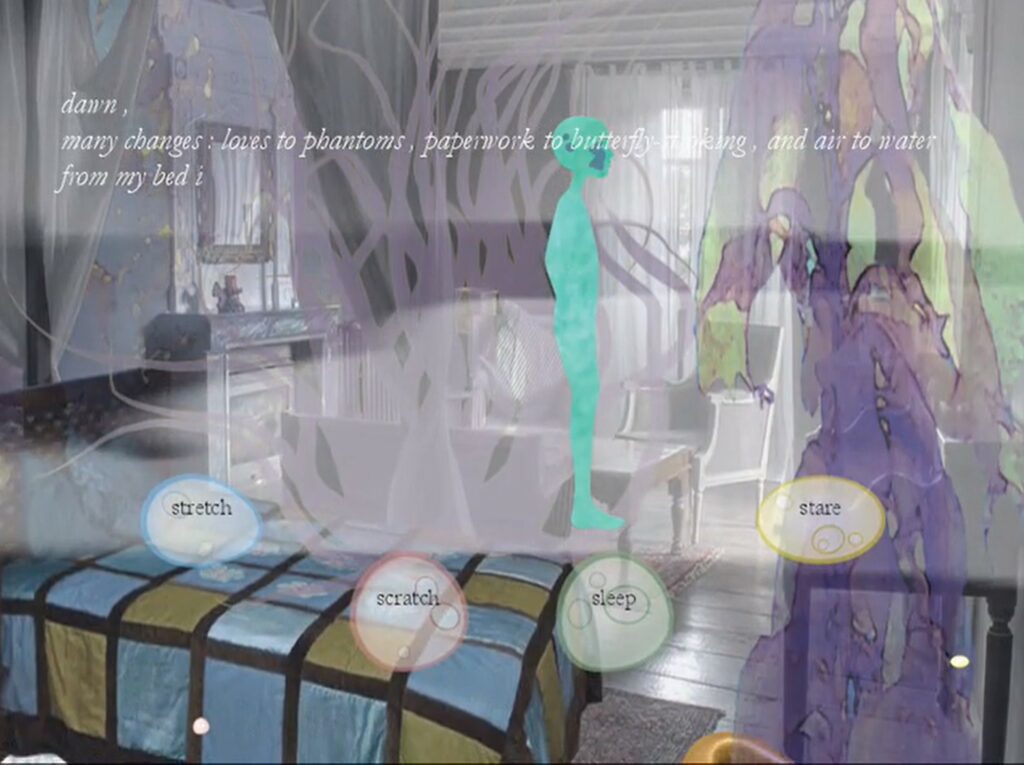

Fox Harrell’s interactive narrative Loss, Undersea.

Sponsored by the Modern Language Association’s Executive Committee on Screen Arts and Culture, this exciting and well-attended session on environmental media built on growing institutional and scholarly interest in radically expanding notions of media and mediation to comprise not only traditional mass media and broadcasting but also bodies, landscapes, and natural processes. The panelists’ presentations collectively explored new methods, case studies, and interdisciplinary connections in the environmental humanities, each with a distinct elemental bent—earth, wind, water, oil—across diverse historical periods and literary and material sites. Mukherjee began by treating soil as a “mediating element” for labor and cultural anxieties in postcolonial Calcutta, specifically around the construction of the Metro Railway from 1969 to 1984. Moro then directed our attention to breath and its potential to open up new kinds of environmental critique, drawing skillfully on Ted Chiang’s 2008 science fiction short story “Exhalation” and the media archaeology of Wolfgang Ernst (substituting “breath criticality” for Ernst’s “time criticality”). Silcox proposed a kind of “submerged reading” practice for literary scholars, via exemplary works of electronic literature (Sea and Spar Between by Nick Montfort and Stephanie Strickland and Loss, Undersea by D. Fox Harrell); this watery method acknowledges climate change-induced sea-level rise and developing work in the “blue” or ocean humanities. Finally, Jones concluded with speculation over whether contemporary work on energy, petrocultures, and critical infrastructure could be fruitfully applied to nineteenth-century energy ecologies, for instance the use of whale oil, using an “energy archaeology” approach (might Herman Melville be considered an energy archaeologist?).

Everyday Ecofascism: Representation and Resistance

Report by Alex Menrisky, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth

Alex Menrisky, Presider

Participants: April Anson (San Diego State University, Matthew Henry (University of Wyoming), Alex Menrisky

From Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite.

This panel (sponsored by the Western Literature Association) examined implicit (rather than overt) expressions of ecofascism—environmentalism of a white-supremacist, anti-immigrant, and/or anti-Native persuasion that advocates for population reduction along lines of race, ethnicity, and/or nation. Addressing myriad, often subtle ways in which white-supremacist and settler-colonial attitudes influence modern environmentalism, as well as marginalized writers’ active role in contesting these influences, the panelists considered the formal, stylistic, and narrative conventions of ecofascism as an environmentalist genre. In “Green Walls: American Ecofascism and Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite,” April Anson illuminated how Parasite “draws a fundamental link between the American nature tradition, Indigenous genocide, and the transnational terror of settler colonialism’s supposed ‘natural’-ness”—all while tracing a genealogy of American ecofascist thought. Matt Henry blended personal history with critical scholarship in “Edward Abbey, Ecodefense, and Ecofascism in the Misanthropocene,” in which he illustrated how Edward Abbey’s trademark misanthropy towards the “teeming masses” living in overcrowded, polluted urban spaces constitutes a dog-whistle for prejudice against people of color and also overlaps significantly with contemporary ecofascist discourse. Lastly, in “Fascist Foodstuffs: Everyday Settler Colonialism and Representations of Consumption,” Alex Menrisky suggested that the poetry of Tommy Pico invites readers to consider the extent to which ecofascism is not a stable right-wing position, but rather a broadly circulating cultural narrative about settler-colonial identity and environment, premised on privileged access to environmental purity at the expense of colonized others on whom that fantasy of access depends. Discussion following the presentations both generously and generatively considered the definition and scope of the term of ecofascism today, as well as its relationship with or contrast to environmental justice—a conversation that reached beyond the session to resurface in others at the conference.

The Infrastructure of Emergency

Report by Jessica Hurley, George Mason University

Presider: Jeffrey Insko (Oakland University)

Participants: John Levi Barnard (University of Illinois, Urbana), Stephanie Foote (West Virginia University, Morgantown), Rebecca Evans (Southwestern University), Leah Becker (University of Illinois, Urbana), Jessica Hurley (George Mason University), Jennifer Williams (Howard University)

The editors of the forthcoming joint special issue The Infrastructure of Emergency (Fall 2021), a collaboration between American Literature and Resilience, convened this roundtable to share work from and related to the project. Jeffrey Insko began the discussion by asking us to consider the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline as an exemplar of infrastructure’s productive contradictions: an environmentally disastrous infrastructure that locks us into local and global ecological emergencies but also a site of conflict and resistance. Jessica Hurley turned the conversation to literature, raising the parallels between infrastructure and literature as structuring forms and suggesting that literature might play a role in creating the desire for infrastructure as a way to be in right relation to others and to the world and negating the toxic individualism that defines neoliberal life. John Levi Barnard also considered how the dystopian valences of infrastructure might be flipped, in this case arguing that a focus on the infrastructures of meat consumption (rather than production) allows us to imagine how these infrastructures might be repurposed to distribute foodstuffs that would mitigate rather than perpetuate our current planetary crisis. Stephanie Foote introduced her new work on “necroinfrastructure”: from the cities literally built on land made of animal carcasses to the fate of the human body after excretion and after death, Stephanie showed how naturalism, in particular, incorporates into its form the externalities of capitalist life that remain unmanageable by infrastructure. Rebecca Evans also drew our attention to form, describing the use of what she calls “gothic geomemory” by contemporary African American novelists as a set of genre innovations that render visible the continuities of plantation infrastructures and their uncanny agency within the present. Leah Becker drew on nineteenth-century housekeeping manuals to show how women conceptualized their work to produce hygiene (and especially ventilation) within the home as central to the development of a healthy nation, a collapse of the distinction between public and private health infrastructures that resonates uncannily with our present moment of COVID. Jennifer Williams concluded the roundtable with her work on June Jordan’s speculative architecture of Black flourishing and her theorization of the poem itself as a potential space for reparation and repair. The session concluded with a lively Q&A – featuring many ASLE members! – covering topics including the relationship between genre and infrastructure and the role of Black art in promoting reparative relationships between human spaces and human lives.

The editors of the forthcoming joint special issue The Infrastructure of Emergency (Fall 2021), a collaboration between American Literature and Resilience, convened this roundtable to share work from and related to the project. Jeffrey Insko began the discussion by asking us to consider the Enbridge Line 5 pipeline as an exemplar of infrastructure’s productive contradictions: an environmentally disastrous infrastructure that locks us into local and global ecological emergencies but also a site of conflict and resistance. Jessica Hurley turned the conversation to literature, raising the parallels between infrastructure and literature as structuring forms and suggesting that literature might play a role in creating the desire for infrastructure as a way to be in right relation to others and to the world and negating the toxic individualism that defines neoliberal life. John Levi Barnard also considered how the dystopian valences of infrastructure might be flipped, in this case arguing that a focus on the infrastructures of meat consumption (rather than production) allows us to imagine how these infrastructures might be repurposed to distribute foodstuffs that would mitigate rather than perpetuate our current planetary crisis. Stephanie Foote introduced her new work on “necroinfrastructure”: from the cities literally built on land made of animal carcasses to the fate of the human body after excretion and after death, Stephanie showed how naturalism, in particular, incorporates into its form the externalities of capitalist life that remain unmanageable by infrastructure. Rebecca Evans also drew our attention to form, describing the use of what she calls “gothic geomemory” by contemporary African American novelists as a set of genre innovations that render visible the continuities of plantation infrastructures and their uncanny agency within the present. Leah Becker drew on nineteenth-century housekeeping manuals to show how women conceptualized their work to produce hygiene (and especially ventilation) within the home as central to the development of a healthy nation, a collapse of the distinction between public and private health infrastructures that resonates uncannily with our present moment of COVID. Jennifer Williams concluded the roundtable with her work on June Jordan’s speculative architecture of Black flourishing and her theorization of the poem itself as a potential space for reparation and repair. The session concluded with a lively Q&A – featuring many ASLE members! – covering topics including the relationship between genre and infrastructure and the role of Black art in promoting reparative relationships between human spaces and human lives.

Persistent Ecologies: Responding to Environmental Injustices (ASLE-sponsored session)

Report by Clare Echterling, Caldwell University

Presider: Clare Echterling

Participants: Susie O’Brien (McMaster University), Catriona Sandilands (York University), Jenny Kerber (Wilfrid Laurier University), Cheryl Lousley (Lakehead University)

The presidential theme for the 2021 MLA Annual Convention was “Persistence.” In her statement on the theme, MLA President Judith Butler asked, “what part should literature and language scholars play in uncovering and creating practices of persistence that can lead to new conditions of life in and outside the academy?” ASLE took up this theme and question, organizing the session Persistent Ecologies: Responding to Environmental Injustices with speakers Susie O’Brien (McMaster University), Catriona Sandilands (York University), Jenny Kerber (Wilfred Laurier University), and Cheryl Lousley (Lakehead University), and myself as presider (Clare Echterling, Caldwell University).

The presidential theme for the 2021 MLA Annual Convention was “Persistence.” In her statement on the theme, MLA President Judith Butler asked, “what part should literature and language scholars play in uncovering and creating practices of persistence that can lead to new conditions of life in and outside the academy?” ASLE took up this theme and question, organizing the session Persistent Ecologies: Responding to Environmental Injustices with speakers Susie O’Brien (McMaster University), Catriona Sandilands (York University), Jenny Kerber (Wilfred Laurier University), and Cheryl Lousley (Lakehead University), and myself as presider (Clare Echterling, Caldwell University).

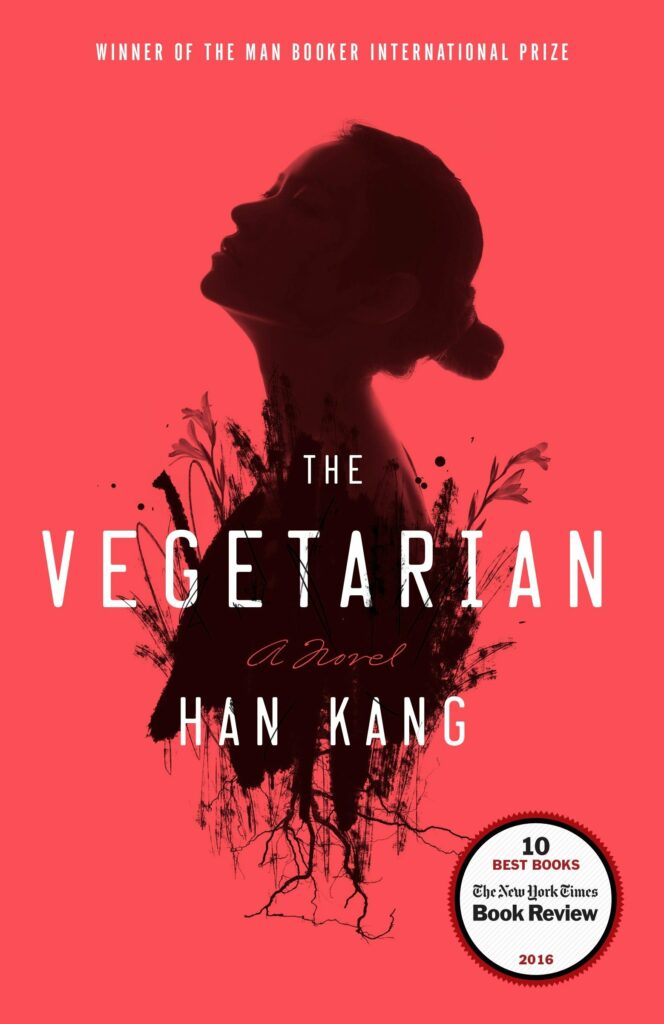

O’Brien’s talk, “Emergent Strategy for Climate Crisis: Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower,” spoke directly to Judith Butler’s question, examining the liberatory strategies of intentional adaptation and persistent survival that Octavia Butler offers in her 1993 climate novel. Sandiland’s presentation, “Sexual Violence and Vegetal Persistence in The Vegetarian and Cereus Blooms at Night,” analyzed Han Kang’s and Shani Mootoo’s respective novels to consider feminist and vegetal forms of persistence, resistance, and modes of being that counter patriarchal, colonial, interspecies, and other types of persistent violence. In “Rethinking Consent in Recent Writing by Indigenous Women,” Kerber showed that the concept of consent is key to understanding relations between Indigenous peoples, land, and settler colonialism in Canada today. While the idea of free and informed consent has become important in the negotiations between Indigenous nations, corporations, and governments regarding development projects, it is hollow. Settler colonial powers do not accept “no” as an answer, persistently whittling away opposition. Kerber then analyzed writing by Indigenous writers Helen Knott, Tunchai Redvers, and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson that offers a decolonial model of consent. Lastly, Lousley’s paper, “Worlds of Endurance: Indigenous Testimonial Speech at the World Commission on Environment and Development,” called us to rethink the testimonial mode by examining the Indigenous testimonies given at the World Commission on Environment and Development in Canada in 1986. These and similar testimonies allow settler states to recognize Indigenous peoples’ political rights and demands, thus appealing to liberal discourses of social inclusion while persistently, incessantly inflicting socio-ecological violence. Together, these four presentations suggested that persistence is a significant topic for environmental humanists and literary scholars.

The Poetics of Air in American Ecological Writing

Report by Orchid Tierney, Kenyon College

Presider: Orchid Tierney

Participants: Jean-Thomas Tremblay (New Mexico State University), Robert Balun (CUNY), Elizabeth McDermott (University of St. Francis), and Orchid Tierney

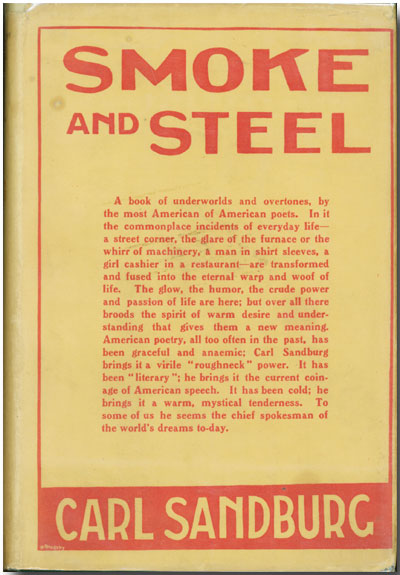

This panel explored how contemporary writers have theorized, literalized, and understood air and respiration with respect to environmental or extractive disturbances. Participants probed into the socio-cultural, racialized, and toxic imaginations of air and breath, and attended to the presence of precarity in ecocriticism, American poetry, and/or experimental writing. Through their readings of Orlando White’s Letterrs and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Jean-Thomas Tremblay’s paper, “Breathing Aesthetics,” pushed generatively against breath as understood within Projectivist circles to propose a framework for an aesthetics of respiration. Next, in “Atmospheric Poetics: (Eco)Poetry in the Anthropocene,” Robert Balun addressed the modern epoch’s conceptualization of existence and dislocation through the lens of Myung Mi Kim’s Civil Bound, Franco Berardi’s Breathing: Chaos and Poetry, and the philosophy of Peter Sloterdijk. Elizabeth McDermott’s paper, “‘Our skies, already browned’: A Study of Metaphoric Restraint in Ammons’ Garbage,” turned to the currents of Emersonian resilience and the literalness of metaphor in Ammons’ landfill-inspired collection. Finally, Orchid Tierney’s paper, “Smoke in the Anthropocene: Bad Air in Carl Sandburg’s ‘Smoke and Steel’” sketched out the intersection of smoke, circulation, and progressive modernities in the twentieth century.

This panel explored how contemporary writers have theorized, literalized, and understood air and respiration with respect to environmental or extractive disturbances. Participants probed into the socio-cultural, racialized, and toxic imaginations of air and breath, and attended to the presence of precarity in ecocriticism, American poetry, and/or experimental writing. Through their readings of Orlando White’s Letterrs and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, Jean-Thomas Tremblay’s paper, “Breathing Aesthetics,” pushed generatively against breath as understood within Projectivist circles to propose a framework for an aesthetics of respiration. Next, in “Atmospheric Poetics: (Eco)Poetry in the Anthropocene,” Robert Balun addressed the modern epoch’s conceptualization of existence and dislocation through the lens of Myung Mi Kim’s Civil Bound, Franco Berardi’s Breathing: Chaos and Poetry, and the philosophy of Peter Sloterdijk. Elizabeth McDermott’s paper, “‘Our skies, already browned’: A Study of Metaphoric Restraint in Ammons’ Garbage,” turned to the currents of Emersonian resilience and the literalness of metaphor in Ammons’ landfill-inspired collection. Finally, Orchid Tierney’s paper, “Smoke in the Anthropocene: Bad Air in Carl Sandburg’s ‘Smoke and Steel’” sketched out the intersection of smoke, circulation, and progressive modernities in the twentieth century.

The initial proposal of this panel had attended to the social construction of “atmospheres” and “air” (as used interchangeably in common parlance) with a nod toward the nascent field of the Atmospheric Humanities. Yet these papers underscored the deep-set conditions of precarity—the racial, colonial, and environmental vocabularies of harm and embodiment—that underpin the air we breathe and the politics of breathing itself. To this end, this panel not only proposed plural encounters with the question “how do we read for air,” but it also offered insights on the labors of breathing in relation to resilience, imperilled bodies, and atmospheric threats.

Romanticism and Wilderness

Report by James C. McKusick, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Presider: Charles Waite Mahoney, University of Connecticut, Storrs

Participants: Markus Poetzsch (Wilfrid Laurier University), Cassandra Falke (Arctic University of Norway), Kyle McAuley (Seton Hall University), Lisa Vargo (University of Saskatchewan)

Respondent: James C. McKusick

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich (1818)

The Wordsworth-Coleridge Association organized a session on “Romanticism and Wilderness.” Each of the four presentations made an important contribution to our understanding of the wilderness concept in the British Romantic period. Markus Poetzsch examined the problematic role of humans in the representation of picturesque landscape. Wild landscapes are supposed to be picturesque, and yet for William Gilpin, the wild is an unpredictable terrain of sudden accidents and surprises that threaten to disrupt the aesthetic pleasures of picturesque tourism. Wilderness emerges here as a disruptive force, proving in the end unamenable to the instruments of “optical hegemony.” Cassandra Falke described Wordsworth’s “Poems on the Naming of Places” as failed acts of naming, and yet, as successful acts of ecopoeisis. These poems connect the unsayability of earth to natural processes that humans can neither control nor know. Drawing on Jean-Luc Marion´s concept of saturated phenomenality, Falke suggested that Wordsworth’s poetry has a wild, self‑generating quality, akin to the wild energies of nature itself. Kyle McAuley elucidated the representation of Scotland’s wilderness borders in the novels of Walter Scott. McAuley discussed the newly-invented mapping technology of “hachures,” which enables the representation of three-dimensional topography on a two-dimensional map. Wilderness is thereby assimilated into known and familiar terrain through the process of mapping. Mapmaking, empire-building, and novel-writing go hand in hand, in a process that ultimately seeks to rationalize and domesticate wilderness. Lisa Vargo suggested that the term “rewilding” might describe the physical and psychological restoration of nature in the journals of Dorothy Wordsworth. Vargo described how the simple act of sitting on the ground drives the development of a deeper and more meaningful relationship between Dorothy and the wild landscapes of the English Lake District. Dorothy’s interest in rewilding is especially apparent in her project to restore the Dove Cottage garden, using local flora transplanted from nearby mountains, woodlands, and farmsteads. All four of these papers raised fascinating questions about the problematic role of humans, and of human perception, in representing wilderness.

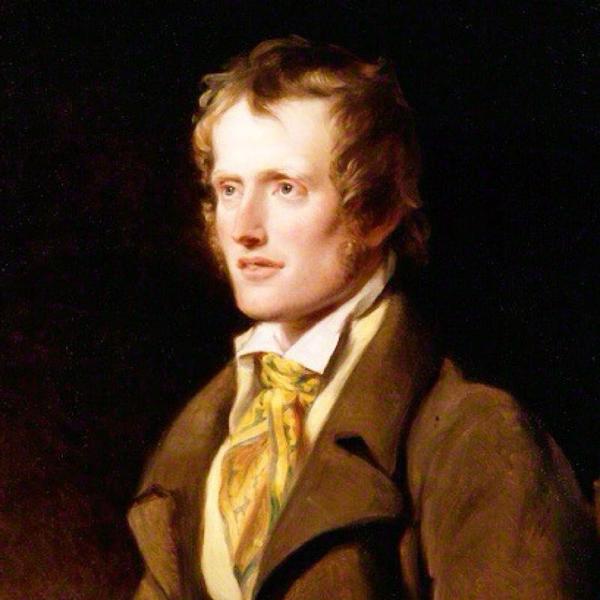

Some Environmental Approaches to John Clare

Report by James C. McKusick, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Presider: James C. McKusick

Participants: Effie GIanitsos (Syracuse University), Lauren Cooper (Syracuse University), Jayme Collins (Northwestern University)

The John Clare Society of North America organized a session on “Some Environmental Approaches to John Clare.” Effie Gianitsos offered an insightful close reading of “The Mouse’s Nest,” highlighting Clare’s distinctive unwillingness to project Enlightenment ideals onto the mouse and the environment. She argued that the poem’s ecology presents a relationship to habitats and habitation that resembles Edmund Burke’s counter-enlightenment ideology. By linking Clare’s aesthetics to Burke’s ideology, Gianitsos expanded our understanding of both thinkers as conservative and conservationist. Lauren Cooper developed a close reading of an important Clare poem, “The Lament of Swordy Well.” Cooper affirmed that this poem articulates a local ecosystem that has been destroyed by human activity, and that it calls out, paradoxically, for humanity to return to this place and re-work it once again. The act of giving voice to Swordy Well disrupts the notion of wilderness as unknowable and distinct from humanity because it relies on the poet’s ability to sympathize with the land itself. Jayme Collins focused on Simon Cutts’s 2004 art installation “After John Clare,” which transforms an old stone pump house into the world’s first wind-powered neon signage. By attaching a wind propeller to the front of the small hut, wiring it to a generator and then to neon lettering installed on the walls within the narrow structure, Cutts encloses a famous line from John Clare’s poetry within its nascent pastoral scene: “I found the poems in the fields and only wrote them down.” Re-articulating Clare’s poem across two centuries, Cutts makes of this line a new “situated” poem in which the place of poetry’s inscription generates its own environmental poetics. The panel was well-attended, and a lively discussion followed the presentations.

The John Clare Society of North America organized a session on “Some Environmental Approaches to John Clare.” Effie Gianitsos offered an insightful close reading of “The Mouse’s Nest,” highlighting Clare’s distinctive unwillingness to project Enlightenment ideals onto the mouse and the environment. She argued that the poem’s ecology presents a relationship to habitats and habitation that resembles Edmund Burke’s counter-enlightenment ideology. By linking Clare’s aesthetics to Burke’s ideology, Gianitsos expanded our understanding of both thinkers as conservative and conservationist. Lauren Cooper developed a close reading of an important Clare poem, “The Lament of Swordy Well.” Cooper affirmed that this poem articulates a local ecosystem that has been destroyed by human activity, and that it calls out, paradoxically, for humanity to return to this place and re-work it once again. The act of giving voice to Swordy Well disrupts the notion of wilderness as unknowable and distinct from humanity because it relies on the poet’s ability to sympathize with the land itself. Jayme Collins focused on Simon Cutts’s 2004 art installation “After John Clare,” which transforms an old stone pump house into the world’s first wind-powered neon signage. By attaching a wind propeller to the front of the small hut, wiring it to a generator and then to neon lettering installed on the walls within the narrow structure, Cutts encloses a famous line from John Clare’s poetry within its nascent pastoral scene: “I found the poems in the fields and only wrote them down.” Re-articulating Clare’s poem across two centuries, Cutts makes of this line a new “situated” poem in which the place of poetry’s inscription generates its own environmental poetics. The panel was well-attended, and a lively discussion followed the presentations.

Structures of Legibility: Emerging Approaches to Energy and Infrastructure (ASLE-sponsored session)

Report by Jordan B. Kinder, McGill University

Presider: Jordan B. Kinder

Participants: Jacob Goessling (Christian Brothers University), Katherine Hummel (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), Reuben Martens (KU Leuven), Kyle McAuley (Seton Hall University)

Respondent: Andrew B. Ross (Johns Hopkins University, MD)

This ASLE-sponsored roundtable was organized by Jacob Goessling, Andrew B. Ross, and myself as an opportunity to bring together emerging voices in infrastructure studies and the environmental humanities and to create space to think through the limits and possibilities of existing approaches to energy and infrastructure in the humanities, as well as generate some new approaches and vocabularies for doing so.

AMD&Art Project in Vintondale

Vintondale, PA, 1995 – 2005. Image by Stacy Levy.

Jacob Goessling began the roundtable with a meditation on remediation infrastructure. Goessling critically read two remediation projects against and with one another—a recreational park built on a formerly active coal mine in western Pennsylvania called AMD&Art Park and US Penitentiary, Big Sandy, which was built on an abandoned mine site a few hundred miles south in Martin County, Kentucky, where extractive capitalism is remediated as carceral capitalism. The two landscapes, Goessling argued, share a common ideological function by hiding the magnitude of extraction’s environmental and social impact. Following Goessling, Katherine Hummel asked “how literature apprehends and responds to ambiance,” noting that the ambient operation of infrastructure has served as a problem for literary critics who often rely on infrastructural breakdown or exception as analytic focal points. Turning to Mohsin Hamid’s 2013 novel How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia, Hummel drew upon Jennifer Wenzel’s introduction of legibility and intelligibility as ways to address infrastructure in texts where infrastructure is more ambient than spectacular. While Hamid’s novel is not an infrastructural novel at first glance, Hummel revealed how water infrastructure serves an ambient, yet instrumental role in the form and content of the narrative. Reuben Martens followed Hummel by inviting us to think through the temporal politics of infrastructure through the concept of “infrastructural prolepsis.” Grounded in a project that he worked on with Pieter Vermeulen, Martens approached infrastructure objects of temporal apprehension and affective investment in Karen Tei Yamashita Tropic of Orange (1997) and Ben Lerner’s 10:04 (2014). Focusing on the theoretical dimensions of the project, Martens framed infrastructure as a tenuous site of hope for futures beyond the apocalyptic. Following Martens, Kyle McAuley proposed “critical hydrography” as a means of uncovering the forms of hydrographic infrastructure in literary works. Performing a brief analysis of a passage from Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo (1904), McAuley explored what geologic thinking offers to an anti-racist environmental humanities.

Andrew B. Ross closed the roundtable with a response that synthesized the shared trajectories of the contributions and anticipated the discussion period by drawing attention to the methodological questions that were raised in the roundtable surrounding what it means to see infrastructure. Ross concluded by proposing another key term to the roundtable’s lexicon of reading practices: the bioregional concept of reinhabitation, which he argues opens up possibilities for understanding the lived experiences of infrastructure at the scale of the watershed. The discussion that followed picked up on these threads by creating space for further reflection on the theoretical and methodological interventions the roundtable collectively put forward and tarried with what it means to be doing environmental humanities work today.

Many other important topics in the Environmental Humanities were also covered at MLA this year, including these panels:

Queer Ecologies

Sponsored by the TC Ecocriticism and Environmental Humanities Forum

What new ways of thinking, making, and living reveal themselves through queer ecological perspectives? Such perspectives critique normative categories of nature and generate new nature-culture assemblages against dominant ecological regimes. We have outplayed the current mode of understanding nature-culture, and it is time for queer ecologies.

Presenters:

Nicole Seymour, California State University, Fullerton

Joseph Campana, Rice University

Travis Alexander, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Greta Gaard, University of Wisconsin, River Falls

Respondent: Catriona Sandilands, York University, Keele

Populism and the Climate Emergency: Rereading Modest Witness

Presider: Cheryl Lousley, Lakehead U, Orillia

Presenters:

Dear Quora, Where Does It End? Populist Anxiety and the Remedy of Postscience Speculation

Jody Berland, York University

Kim Stanley Robinson and the Climate Crisis

Douglas Ivison, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay

True Crime: Climate Change’s Documentary Aesthetic

Daniel W. Worden, Rochester Institute of Technology

Canadian Environments and the Extraction Economy

Sponsored by the TC Ecocriticism and Environmental Humanities Forum

Panelists consider the literary cultures and histories of resource extraction in Canada, asking how literary works and other forms of cultural production respond to material cultures and histories of resource extraction, especially in relation to Indigenous rights and territory.

Presider: Nicholas Bradley, University of Victoria

Presenters:

Andrew Brown, Dalhousie University

Dallas Hunt, University of British Columbia, Vancouver

David Huebert, University of King’s College, Halifax

Emily McGiffin, University College London

Max Karpinski, University of Alberta

Rebecca Macklin, University of Pennsylvania

Mohebat Ahmadi, University of Melbourne

Environmental Humanities in Spanish and Portuguese 2.0

Presider: Gwendolyn Barnes-Karol, St. Olaf College

Presentations:

Ecopoetics in Contemporary Spain

Candelas Gala, Wake Forest University

Vegetal Ontologies and the Baroque in Alejo Carpentier’s Los pasos perdidos

Fernando Varela, Vanderbilt University

‘A Cielo Abierto’: Extractivism in the Work of Roberto de la Torre

Eva-Lynn Alicia Jagoe, University of Toronto

Animal Locution and the Agency of the Nonhuman: An Amazonian Poetics in Embrace of the Serpent

Juan Pablo Cárdenas, U of Pennsylvania

New Approaches to Early Modern Environmental Catastrophism

Presider and Respondent: Laurie Shannon, Northwestern University

Presentations:

The Erotics of Salvage

John Yargo, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Ophelia’s ‘Good End’: Water and Ecosexual Desire

Lisa Robinson, St. John’s University, NY

Ben Jonson’s New World Humors

Caro Pirri, University of Pittsburgh

Cryptodormancy

Ellen MacKay, University of Chicago