By Elizabeth Carolyn Miller

“Follow the money,” a familiar phrase associated with Watergate and with political crime and corruption more generally, could also be described as an underlying method of my new book, Extraction Ecologies and the Literature of the Long Exhaustion. This is a book of literary criticism, not economic history, a book concerned with narratives rather than numbers; yet in my selection of its topic and of the fifteen primary literary texts on which I focus, money was an early guide. I began my research in the early 2010s, when I was broadly interested in writing an environmental study of long-nineteenth-century literature that was attentive to what geographer Bruce Braun calls “social natures” and to the interpenetrated histories of capitalist growth and environmental catastrophe.

“Follow the money,” a familiar phrase associated with Watergate and with political crime and corruption more generally, could also be described as an underlying method of my new book, Extraction Ecologies and the Literature of the Long Exhaustion. This is a book of literary criticism, not economic history, a book concerned with narratives rather than numbers; yet in my selection of its topic and of the fifteen primary literary texts on which I focus, money was an early guide. I began my research in the early 2010s, when I was broadly interested in writing an environmental study of long-nineteenth-century literature that was attentive to what geographer Bruce Braun calls “social natures” and to the interpenetrated histories of capitalist growth and environmental catastrophe.

What initially brought me to the specific topic of extraction, however, was a recognition of how many of the authors I work on were able to write because of money from mines. The family fortune of William Morris, pioneer of Arts & Crafts and eco-socialism, came from shares in the Devon Great Consols copper mine – shares of which he would eventually divest himself. J.R.R. Tolkien was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa where his English father had taken a position with the Bank of Africa, whose primary business was the funding of diamond and gold mines during the period of South African history known as the Mineral Revolution. H. Rider Haggard, author of King Solomon’s Mines (1885) and other popular adventure romances, invested in Mexican copper mines and even attempted, with a friend, to mount a search for Montezuma’s legendary lost treasure in Mexico. As my book developed, my roster of authors would expand beyond the investor class to include writers from the colonies, women writers, and writers of color, but as I researched further I found that no writer from the period, and no text, was untouched by the imperial project of mineral resource extraction.

My analysis in Extraction Ecologies is qualitative rather than quantitative, more attentive to the nuances of genre and text than to profits and losses, but these biographical details were my first clue that the literature I study is closely bound up with the rise of industrial mining. The specific period on which my book focuses begins in the early 1830s with the decisive shift to steam power in British manufacturing and distribution and ends in the late 1930s with the dawn of the nuclear era. What I hope to capture with this chronology is a period when Britain came to understand itself as an empire thoroughly dependent on extraction: an extraction-based society, bound up with the mining of underground material, with no viable alternative capable of preserving existing social relations.

A central premise of my study is that the extraction of underground mineral resources – not only coal, but gold, iron, tin, copper, silver, and more – can be conceived of as a singular activity, and that this activity of extraction was bound up with a new cluster of socio-environmental conditions: extractivism. “Extractivism” names a complex of cultural, discursive, economic, environmental, and ideological factors related to the extraction of underground resources on a large, industrial scale. Two major similarities yoke together various forms of mineral resource extraction as a singular activity in this period. First, extraction of all kinds relied on the use of steam for the draining of mines, crushing of ore, and transport of commodities. Virtually every technological component of the extraction supply chain was accelerated phenomenally by steam, and thus the much-discussed accelerated extraction of coal in the early nineteenth century led to more intense exploitation of all subsurface resources, and vice versa. Secondly, all such underground resources were connected by their material finitude, and finitude and non-reproducibility, above all, distinguish mineral resource mining as an extractive process.

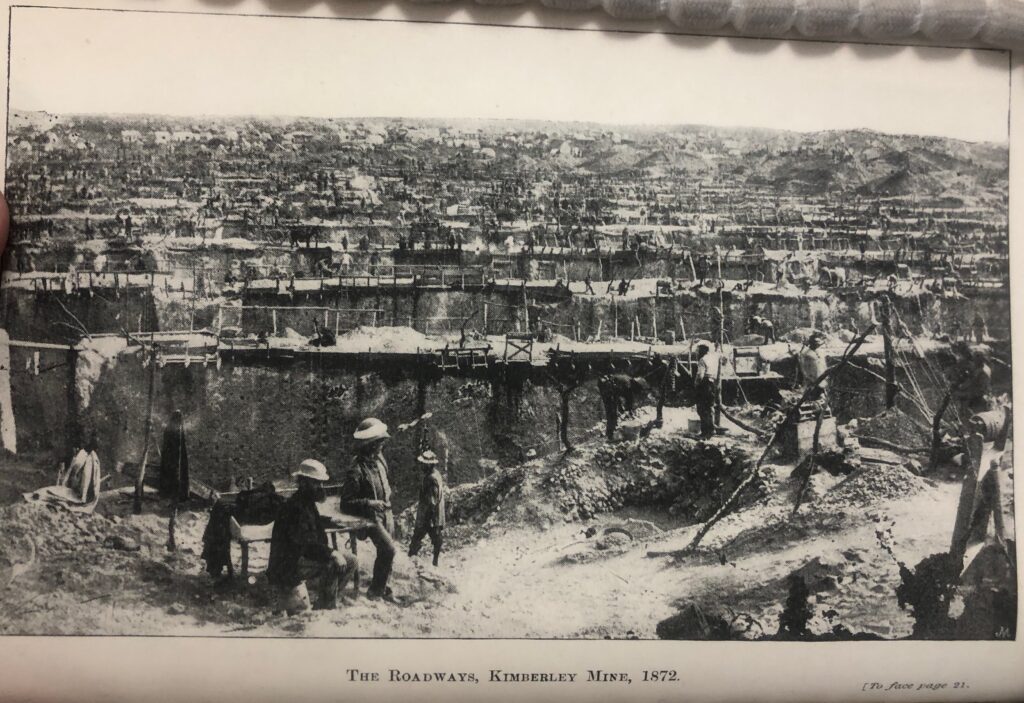

“The Roadways, Kimberley Mine, 1872,” from Reunert’s Diamond Mines of South Africa (London: Sampson Low, Marston; Cape Town: J. C. Juta, 1892), 20.

Extractive industry can never benefit from regeneration or replenishment, but can only move on to a new vein or site, and for this reason metal and mineral resources were defined in economic terms by their special lack of regenerative capacity. As W. Stanley Jevons put it in his 1865 book The Coal Question: An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal Mines, “A farm, however far pushed, will under proper cultivation continue to yield for ever a constant crop. But in a mine there is no reproduction, and the produce once pushed to the utmost will soon begin to fail and sink to zero” (154-55). My work focuses on the extraction of underground mineral resources because, as this quotation suggests, the mining industry presents the overwhelmingly dominant example of resource finitude in the context of historical thought from the 1830s to the 1930s. An extraction-based society, economically grounded in the extraction of finite materials, was understood to mean a society that was, in a new way, unsustainable for the long run. Thus literature of the industrial era was in the remarkable position of confronting, ideationally, the mode of life that we all experience today, a mode of life that proceeds by depleting the future.

Mineral resource exhaustion did not turn out to be the fatal flaw of fossil-fueled industrialism that many thinkers at the time predicted – to the contrary, we have far too much coal, for example, than is at all good for us – but mineral resource exhaustion did occasion early reflection on the unsustainability of extraction ecologies, and the literary archive shows that even in its early days extraction-based life was understood as a future-depleting system. My book takes up the question of what it has meant for us, as a linguistic community, to be immersed in a culture and literature so thoroughly saturated in extractivism and its assumptions about the Earth and the future. Have two hundred or more years of extractivist language and literature prepared us, in some way, for the crisis we now face? Or have they made environmental crisis seem inevitable, and thus encouraged complacency?

In establishing the extent to which extractivism permeates literary form and genre in the industrial era, my book shows how culture, language, and discourse carry along the assumptions that emerge under one set of material-environmental conditions into the new stage that follows. I take form and genre to be important objects of environmental analysis because they are epistemological structures that embed our fundamental conceptual formations, and what is more, they are mobile and repeatable across time and space. Because of the durational qualities of language and form, literature engages with environmental materiality across time, and is thus a crucial archive for understanding extractivism.

Black Country Landscape by Edwin Butler Bayliss (1874-1950), Wolverhampton Art Gallery.

We can take a step back, however, to ask why we need to understand extractivism in the first place, or why we need to understand it in historical terms. Extraction is one of the great challenges of our environmental moment. Around the world, Indigenous groups have been mobilizing around a new politics of anti-extractivism, and in the United States, protests against the Dakota Access and other major pipelines have provided some of the most vivid, hopeful scenes of environmental activism in recent years. And yet the environmental politics of extraction are complex. We are pressed on the one hand with the urgent need to decarbonize and to keep remaining hydrocarbon reserves in the ground if we want to avoid runaway climate change, and on the other hand with the inconvenient reality that the leading contenders to replace the energy of fossil fuels – renewables with battery – also require a great deal of extraction, including materials extracted under especially exploitative or polluting conditions, such as cobalt or rare earth metals. Even nuclear power, an especially controversial substitute for fossil fuels, relies ultimately on uranium extraction, the dangers of which are well documented.

Because of this complexity, extraction is a subject particularly suited for what we might call the slow activism of scholarship and scholarly exchange. A traditional academic monograph is, perhaps, not as immediate a means of engagement as we find in the classroom or in public-facing work, but it does allow for in-depth deliberation over complex subjects. For the purposes of this feature, ASLE asked me, “How does your research help the field, the public, and/or the planet?” The answer is that my book does nothing alone, and yet I hope it can contribute to a longer, slower, more collective and more fundamental change in our ways of thinking about the Earth and our habits of extracting it.

Perhaps scholarship and its slow timelines and far-off horizons seem ill-suited for a moment of urgency, when the future seems so radically foreshortened and endangered. This way of thinking and feeling changed for me as I was writing the book, during a period of dramatically accelerating catastrophe. I drafted the earliest-written section of the book in 2014, for example, but we did not really enter the age of California megafires – the conditions of which are now a defining feature of my life – until 2017 or 2018. The eight biggest wildfires in California history have all happened since December 2017. When I started this book, I was thinking about climate change as a threat to the future – the near future, but still the future; as I worked on it, the future overtook me. Long, slow, scholarly timeframes perhaps no longer seem so available to us. And yet if there is one thing that a historical approach to literature of the environment can offer, it is a reason to hold onto that anti-apocalyptic sense that we don’t know how this story will end. Historical literatures and historical reflections are reminders of contingency, of transformation, of change. 150 years ago, fossil fuel emissions were only starting that upward bend on the familiar hockey-stick graph. The lesson of the long view is that the world can change.

Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, who goes by Liz, is a professor of English at the University of California, Davis, where she teaches classes in nineteenth and early-twentieth-century literature of the British Empire and in the environmental humanities. Her third monograph, titled Extraction Ecologies and the Literature of the Long Exhaustion, appeared with Princeton University Press just a few weeks ago. Her second book, Slow Print: Literary Radicalism and Late Victorian Print Culture (2013) was named Best Book of the Year by the North American Victorian Studies Association and received Honorable Mention for the Modernist Studies Association Book Prize. In 2018 Liz guest-edited a special issue of Victorian Studies on “Climate Change and Victorian Studies.” Her research has been supported with fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the American Council of Learned Societies. Liz descends, on the maternal side, from Italian immigrants who settled in Michigan in the 1920s to mine the Iron Range.

Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, who goes by Liz, is a professor of English at the University of California, Davis, where she teaches classes in nineteenth and early-twentieth-century literature of the British Empire and in the environmental humanities. Her third monograph, titled Extraction Ecologies and the Literature of the Long Exhaustion, appeared with Princeton University Press just a few weeks ago. Her second book, Slow Print: Literary Radicalism and Late Victorian Print Culture (2013) was named Best Book of the Year by the North American Victorian Studies Association and received Honorable Mention for the Modernist Studies Association Book Prize. In 2018 Liz guest-edited a special issue of Victorian Studies on “Climate Change and Victorian Studies.” Her research has been supported with fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the American Council of Learned Societies. Liz descends, on the maternal side, from Italian immigrants who settled in Michigan in the 1920s to mine the Iron Range.