By Paul Huebener

In the era of climate change and ecological collapse, the need to understand how time works in the environment is more important than ever. The habitats of trees are shifting north more quickly than the trees can spread their seeds. Animals that used to be active during the day are becoming nocturnal to avoid us. The climate enters newer and stranger forms of breakdown.

In the era of climate change and ecological collapse, the need to understand how time works in the environment is more important than ever. The habitats of trees are shifting north more quickly than the trees can spread their seeds. Animals that used to be active during the day are becoming nocturnal to avoid us. The climate enters newer and stranger forms of breakdown.

And yet, the narratives circulating within our lives – our everyday ways of imagining ecological and cultural time – are failing us. We can’t seem to grasp the plodding sequence of events between carbon emissions and the resulting heat, yet we also cannot cope with the shockingly fast onset of climate disasters. Our problematic visions of time even affect our own bodies; we go about our daily work as though electric lights and always-connected smartphones make the setting of the sun irrelevant, yet our bodies crave nightly darkness and sleep.

The figurative clocks that tick around us – the delicate forms of time within ecosystems and human cultures – contain great potential for imaginative responses and reconstruction. Like it or not, we are all clockmakers faced with the task of rebuilding our knowledge of environmental time, a prospect simultaneously terrifying and exhilarating. Nature’s Broken Clocks examines how the clocks of nature and culture have become broken, and it shows how we can approach the environment through a critical literacy of the temporal imagination. Readers of the book will expand their ability to reimagine time.

Critical time studies – or, in this case, ecocritical time studies – is a vibrant area of research, and it inspires connections between reading and action. In the classroom, students can examine diverse cultural narratives of time, from novels and poems to advertisements and political statements. Oil pipeline controversies, for example, reveal that pipelines are both cultural objects and sites of contested narratives. An oil pipeline is a spectacular timepiece, turning one of the most ancient, slow-forming substances on earth into a stunningly rapid flow for fast economic muscle and setting us on a long path into an alien future of collapsing climate systems. Ultimately, narratives of oil pipelines are not just about fast versus slow; they are about time as power. The process that a society develops to approve or reject such projects can be understood as a series of debates about what kind of time the pipeline will measure out and how this stacks up to the larger narratives of time we choose to value.

Students engage passionately with time, and the possibilities for assignments and projects are endless. Once students have had some practice assessing diverse representations and accounts of time, they can find their own examples of cultural and literary texts and practices as well as ecological forms of time. In this regard, Michelle Bastian’s definition of the clock is very useful; a clock is “a device that signals change in order for its users to maintain an awareness of, and thus be able to coordinate themselves with, what is significant to them” (italics in original).

We soon find that every object is a clock. A slice of cheddar cheese is a clock that signals the slow erosion of the caves at the village of Cheddar in Somerset, the evolving history of dairy farm agriculture, the maturing process for aging the cheese, the climate disruptions caused by methane from the cows, and the accelerative market forces of globalization. By Bastian’s definition, the only thing that stands in the way of our understanding every object as a clock is our own consciousness. As soon as we see the ballpoint pen or the shrink-wrapped cucumber as a signal of the temporality of plastic, it becomes a device that operates “in order for [us] to maintain an awareness.” We might expand Bastian’s definition by suggesting that every narrative, every action, every process, functions as a clock in waiting even if we don’t notice it.

Telling time with cheddar. What “clocks” will students find? (Photo: Marco Verch)

The fact that our orientation toward time is shaped not just through watches and clocks but through any object we might stumble across is a parallel to the way that our temporal imaginations are shaped not just through the elegant gearwheels of poetry but through the stories we encounter daily in such mundane places as advertisements and political news releases. An object doesn’t need gearwheels to be a clock, and narratives are not just things we find in novels. Amidst all of this, the process of reading poems – both those with an explicit interest in time and those through which temporality emerges as cultural politics – can remain central, teaching us to be alert to the poetry of the diverse times that surround us.

The practice of reimagining time can and should startle us into seeing the world with fresh eyes. Susie O’Brien at McMaster University has delighted her students by asking them to develop personal time experiments, where each student chooses a way to engage with time in an unexpected or unfamiliar way. When I adapted this exercise in an undergraduate seminar, one student decided to adopt the pre-industrial European practice of sleeping in two segments at night with a period of wakefulness in between. She then wrote about how the experiment had freed her from certain temporal assumptions but also created tensions in the clash between different approaches to time (her roommate didn’t like the experiment). These projects can be contextualized through critical and theoretical readings such as Hartmut Rosa’s Social Acceleration, Sarah Sharma’s In the Meantime, and David Farrier’s Footprints.

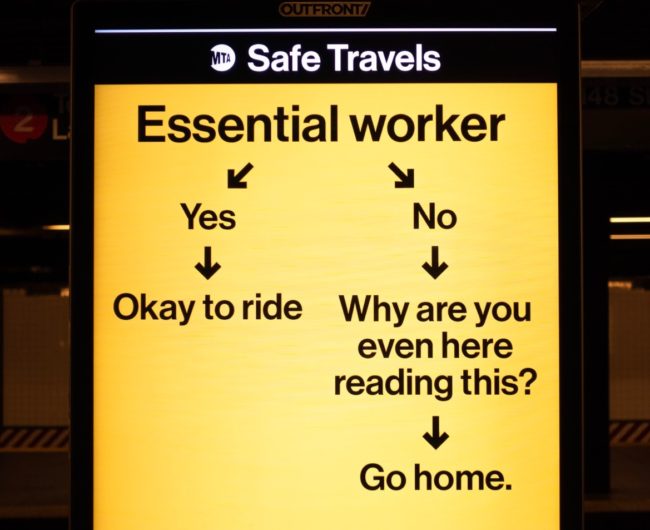

The COVID-19 lockdowns have created a forced experiment in using time differently. The pandemic has thrown our assumptions of time out the window, both in terms of daily routines and in terms of the larger vision of cultural “progress.” Many people no longer have jobs to go to, while others – disproportionately women and people of color – are compelled to work in jobs facing daily hazards for low pay. Teenagers with asynchronous home schooling who have no need to be awake during the day have been switching to nocturnal patterns. New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern is asking employers to consider a four-day work week to boost the domestic tourism industry with longer weekends. The pandemic requires us to use our temporal imaginations differently, and it emphasizes what critical time studies has often recognized, that experiences of time are marked by inequities, privilege, and power. Is lockdown time characterized by boredom or terror? Days on video calls or days on a ventilator? Time, as ever, is an expression of power and powerlessness. It is both imagination and reality.

Pandemic time: bored and depressed at home, or facing daily hazards? (Photo: Daniel Lee)

The near-instantaneous social changes of the lockdown can all too easily invite a confirmation bias. People who want to see fast action on climate change may say, “I knew it! Fast social change is possible!”, while those who resist climate action may say, “I knew it! Fast social change destroys the economy!” We need a nimbleness of the imagination to sort through our choices and their consequences. As thoughtful readers, we can invite an opening up of time, a new sense of temporal imagination and a new willingness to interrogate the links between time, power, and justice. Every narrative has something to say about our encounters with time, and the process of thoughtful reading can discern which forms of time might hold together in a diverse and fragile world. Every story is a clock, and we must tell the time every day.

Photo: blumpics

Paul Huebener’s new book is Nature’s Broken Clocks: Reimagining Time in the Face of the Environmental Crisis. His previous book, Timing Canada: The Shifting Politics of Time in Canadian Literary Culture, was a finalist for the Gabrielle Roy Prize. He is also a co-editor of Time, Globalization and Human Experience. He is an Associate Professor of English at Athabasca University.