ASLE’s Scholar of the Month for January 2024 is Isabel Lane.

My name is Isabel Lane, and I’m a scholar and teacher working at the intersection of literature, technology, incarceration, and environment. I’m currently a Lecturer in the Harvard College Writing Program, where I teach topic-based writing courses and am glad to have the relative freedom to work on collaborative projects, nonacademic writing, and scholarship outside of my original field of training.

I received my Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures from Yale, where research for my dissertation, Narrative Fallout: The Russian and American Novel After the Bomb, began my interest in the relationship between massively scaled industrial systems and the environment. A piece of that larger project, “Byproduct Temporalities: Nuclear Waste in Don DeLillo’s Underworld and Vladimir Sorokin’s Blue Lard,” appeared as part of an article cluster in Russian Literature on Russian culture and the Anthropocene.

After completing my Ph.D., I began working as a faculty member for the Bard Prison Initiative and then became founding program director of the Boston College Prison Education Program. This experience impacted my scholarship, teaching, and thinking about both the environment and prison; it is also how I met my incarcerated collaborator Jared Bozydaj, and together we’ve developed a project, Products of Our Environment (POE), that aims to create a space for people inside and outside of prison to work collaboratively on EJ issues.

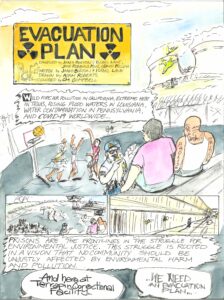

I was previously a Visiting Researcher at the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities and am currently a participant in the Intersecting Energy Cultures Working Group there. In part through that support, my collaborators and I produced a graphic novella, Evacuation Plan, about incarceration and/as environmental injustice.

How did you become interested in studying ecocriticism and/or the environmental humanities?

My early interest in the environmental humanities came out of my doctoral research on nuclear technologies and their effect on space, time, and narrative. I started by thinking about the nuclear in terms of technological development and the military-industrial complex, but (in part through the guidance of incredible mentors like Anindita Banerjee in EH and Marta Figlerowicz in narrative theory) my research ultimately turned to the methodologies and emphases of environmental and narrative effects rather than technological causes.

My work, both in and outside of the academy, has been varied, from a Ph.D. in Russian literature to college in prison to collaborative projects with scholars and artists. But the field of environmental humanities is really what unifies the research, teaching, and less traditional work I’ve done. These could have been divergent paths, but they’ve been united by the undercurrent of environmental harm and the massively scaled systems—nuclear and carceral—that produce it.

Who is your favorite environmental artist, writer, or filmmaker? Or what is your favorite environmental text? Why?

Some of my favorite works of prison-environmental fiction are Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room, Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing, Curtis Dawkins’ The Graybar Hotel, and Varlam Shalamov’s Kolyma Stories. Nonfiction writers and activists like Mumia Abu-Jamal and, before his death, George Jackson also elucidated environmental issues in prison, even if they’re not often categorized as environmental writers. I should also mention the incredible Tim Young here, whose essays, poetry, visual art, and work on the Solitary Garden project (with jackie sumell) offer a unique perspective on prison, environment, and prison abolition.

As part of Products of Our Environment, my collaborator Jane Robbins Mize and I have been working on a syllabus of literature, nonfiction, and art at the intersection of prison and environment. We’ve been featuring some of these readings in our mailings—Jimmy Santiago Baca’s “The New Warden,” Yassin Mohammed’s prison drawings, and Curtis Dawkins’ “Brother Goose.” In addition, we’re putting together a fuller syllabus and, ultimately, a reader that incarcerated folks can request. So please do check our website for more books, texts, and images we love!

I also want to highlight a favorite from Slavic: Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal’s The Tragic Menagerie. It’s somewhere between a novel and a collection of short stories about a young girl coming of age in the Russian countryside. She’s a member of the nobility, and she becomes aware of the injustices of her world largely through her interactions with nature, wild animals, and people—often peasants—she encounters in the fields and woods. It’s truly a remarkable book (and was translated and almost singlehandedly rescued from obscurity in both the Russian-and English-speaking worlds by the amazing Jane Costlow). It is a strange, lyrical book about human cruelty, meddling with nature, and the inseparability of human and environmental fates.

What are you currently working on?

I’m really fortunate to be working with a number of amazing scholars and artists, all of whom have inspired me with their commitment to environmental justice and to the politics and practices of collaboration.

I am currently involved in three projects under the umbrella of the collaborative Products of Our Environment (POE) that incarcerated writer Jared Bozydaj and I began several years ago: first, a series of mailings featuring readings, drawings, and responses from readers; second, a graphic novella called Evacuation Plan about prisons and environmental catastrophe; and third, a research project about prisons, electricity, and sustainability initiatives.

By way of background—when we started POE, Jared and I wanted to create an educational platform that would focus on the environment and would address and resist some of the problems with both saw in prison education, something we had each taken part in as student and administrator respectively. We wanted to experiment with a model that built collaborations between incarcerated people and people outside of prison, something that is actively forbidden in most (if not all) prison volunteering settings. We began working on a syllabus, readings, and discussion questions that could form the backbone of an incarcerated-led reading group.

Things really started to come together when POE was selected to participate in the Intersecting Energy Cultures (IEC) Working Group. Working with the IEC, convened and run by Bethany Wiggin and Rebecca Macklin, has been incredibly generative, and I’m learning so much from others’ projects. I began with a vague idea of studying prisons and energy, and I started by looking into the history of how New York prisons are powered. I stumbled upon the fight to decommission the Indian Point nuclear plant and how its proximity to Sing Sing Correctional Facility was used to argue for the plant’s closure. The prison had no clear evacuation plan in place, nor could one be reasonably implemented in the event of a nuclear accident.

With this history in mind, we (David, Jane Robbins, Jared, and I) began to work with incarcerated artist Adam Roberts and his outside partner Craig (CM) Campbell, together called DrawBreath Studios, to create a long-form comic about a prison sited next to a nuclear plant. It tells the story of two men (and, occasionally, a radioactive goose) in an upstate correctional facility who begin wondering if their prison has an evacuation plan in case of an environmental emergency. Their investigation—through conversation, the prison library, and an ill-fated Freedom of Information Act request—shows some of the ways in which incarcerated people experience and fight against the environmental injustice of living in prison during the climate crisis.

Finally, a press release about solar panels in prisons that we came across prompted me and David to take a deep dive into the history of prisons and electricity, and to set it against the contemporary efforts to “green” correctional facilities. We both found the rhetoric of sustainability disturbing when we considered the very real ways—including the electric chair—that electricity has been used to control, punish, and kill imprisoned people. We’re currently working on a short piece about energy justice and prison, but we’re now seeing that there is a much larger project here, too.

What is something you are reading right now (environmental humanities-related or otherwise) that inspires you, either personally or professionally?

As part of my work on Evacuation Plan, I’ve been reading a lot of graphic novels and memoirs. I especially loved Ezra Claytan Daniels and Ben Passmore’s BTTM FDRS, both for its depiction of industrial decay and gentrification and for its really biting, fun satire. Craig, our Evacuation Plan colorist, recommended it, and while it’s not explicitly environmental, I think it powerfully (and beautifully) captures the devaluation of people and environment going hand in hand.

POE was also inspired by Charlie La Greca and Rebecca Bratspies’ Mayah’s Lot, which the POE group read together and used as a way to think about what we wanted to do with our own comic. One thing we came away with, thanks especially to David, was that Evacuation Plan needed to have a clear abolitionist, anti-institutional perspective. Mayah’s Lot advocates approaching environmental injustice through legal battles and local government, and we wanted to make sure we highlighted not only that those methods are often unavailable to incarcerated people, but that they will also not solve the fundamental issue that captivity is environmental injustice.

Is there a scholar in the field who inspires you? Why?

There are so many scholars in the field whose work has impacted and shaped my own, but Ursula Heise’s has been especially influential, particularly as I navigated the move from literature and narrative theory to the environmental humanities. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet is a touchstone for me, and I always use her “From the Blue Planet to Google Earth” chapter to show my students that the methods of literary analysis can be applied to stories, photographs, and technologies alike.

I’m really inspired by the folks I’ve met doing community-engaged work. It’s been a particular pleasure to work with other teams in the Intersecting Energy Cultures Working Group, and in I’ve learned a lot from Jeffrey Insko’s collaboration with Oil and Water Don’t Mix and Azucena Castro, Juan David Reina-Rozo, and Agustín Neko Epiyú project No aire, no te vendas. Energy Sovereignty and Collective Creation in the Context of the Eolic Parks in la Guajira.

I’m also inspired by scholars working on prisons from other disciplinary perspectives (sociology, critical prison studies/carceral studies, geography, Black and Indigenous studies) that can inform the study of literature and the environment. To name just a few—J. Carlee Purdum and her work with the Campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons on heat in Texas carceral facilities; Ki’Amber Thompson, founder of the Charles Roundtree Bloom Project—I loved her article, “Toward a World Where We Can Breathe: Abolitionist Environmental Justice Praxis”; and, of course, scholars like Ruth Wilson Gilmore and David Pellow, whose work has helped to expose and elucidate the deep connection between prisons and the environment.