By Christy Tidwell with Carter Soles

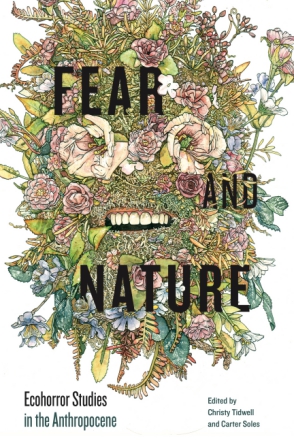

Ecohorror seems to be gaining in popularity and visibility, present both in scholarship on monstrous nature and recent movie releases like Crawl (2019, dir. Alexandre Aja) or In the Earth (2021, dir. Ben Wheatley). This is unsurprising to me. As a genre or mode that reflects human fears of and for the natural world, ecohorror speaks to current concerns about climate change, species extinctions, and the future of the world as we know it. In Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene, Carter Soles and I elaborate on the role ecohorror plays in contemporary media and environmental politics, the various fears it represents, and its relationship to science. We argue that ecohorror

Ecohorror seems to be gaining in popularity and visibility, present both in scholarship on monstrous nature and recent movie releases like Crawl (2019, dir. Alexandre Aja) or In the Earth (2021, dir. Ben Wheatley). This is unsurprising to me. As a genre or mode that reflects human fears of and for the natural world, ecohorror speaks to current concerns about climate change, species extinctions, and the future of the world as we know it. In Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene, Carter Soles and I elaborate on the role ecohorror plays in contemporary media and environmental politics, the various fears it represents, and its relationship to science. We argue that ecohorror

reflects our anxieties about science and the nonhuman while revealing how much we value these things. We fear science and its attempts to control the natural world; we fear the natural world and the way it exceeds our control. We also value science as a way of understanding the world, however, and return to it repeatedly in these narratives; we value the natural world and fear its loss at least as much as we fear nonhuman nature itself. It’s complicated. (7)

To celebrate the release of the book, an edited collection featuring several ASLE members, I invited Carter Soles to have a conversation with me in place of the typical feature ASLE has run for new monographs. Since the book is the result of collaborative effort and reflects the work of many people, a feature written by one person didn’t seem appropriate.

Here, we talk about ecohorror broadly, teaching ecohorror (adding to what others have said in the Teaching Ecohorror series – see Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3), and collaboration.

Christy Tidwell: There has been a real growth in scholarship about ecohorror lately, and it seems to be increasing in popularity. Why do you think that is? What appeals to people about ecohorror, either as fans/audience members or as scholars?

Carter Soles: Ecohorror is a useful mode for understanding our times. It is that simple. The Anthropocene carries with it (so far) an ecohorrific, apocalyptic tone and character – we denizens of Earth are living out a global climate change disaster scenario right now. The works analyzed in Fear and Nature, both popular and literary, are committed to revealing the horror and the possibilities of our present moment. Through the unifying theme of ecohorror, these chapters lay out options for how we can respond to the real-life ecohorrors (what Robin Murray and Joseph Heumann have called elsewhere “everyday eco-disasters“) we experience constantly.

CT: You were already working on ecohorror when I first met you. What prompted your interest in ecohorror? How did you come to it as an interest and a research topic?

CS: For me, it started with horror movies. I became a serious horror movie fan during graduate school, before I even started studying ecocriticism in any kind of focused way. It so happened that many of my closest friends in graduate school were focused ecocritics (this was University of Oregon) and so I was hanging around with ASLE people even before I knew there was an ASLE. Then, in 2009, one of those friends, Steve Rust, suggested I come to the ASLE Biennial Conference in Victoria, BC, which I did, presenting on ecocritical themes in 1970s rural slashers. From then on, my scholarly focus has been entirely on ecomedia criticism. Starting with that conference, I have been an ecohorror cinema specialist from the very beginning of my ecocritical career.

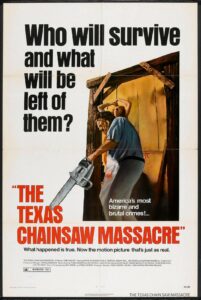

I should also point to the moment that set me on my path: reading Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chain Saws (a must-read for any horror and/or gender studies scholar) and her discussion of “urbanoia,” defined as the city dweller’s fear of rural and wilderness spaces. Clover notes that in horror cinema “the city always approaches the country guilty” (128). That idea, of urban/cosmopolitan guilt over environmental exploitation, is a great encapsulation of horror in general, of ecohorror in particular, and of our present moment. Guilt over runaway fossil fuel exploitation and our failure to act upon abundant warning signs characterizes our culture’s relationship to the nonhuman world in real life.

I would ask you the same question: what first drew you to ecohorror studies?

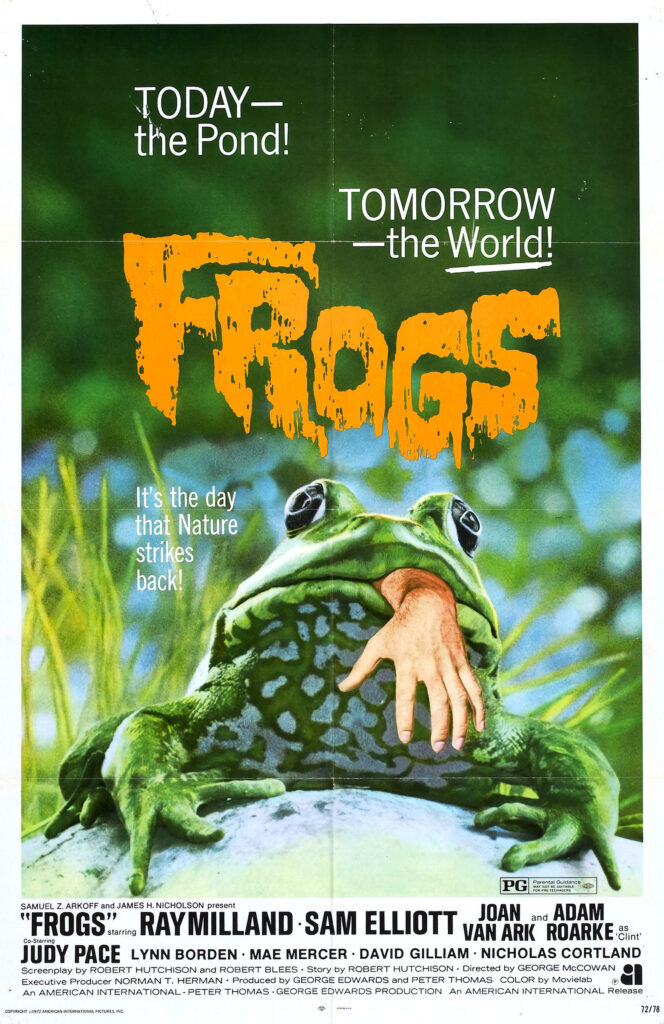

CT: I think I came to it from the opposite direction you did! I was working with ecocriticism first (studying with Stacy Alaimo at the University of Texas at Arlington) and began my work on speculative fiction with science fiction rather than horror. My shift into horror came through creature features. During grad school, I started regularly watching terrible creature features with friends – e.g., Sharktopus (2010, dir. Declan O’Brien), Megashark Vs. Crocosaurus (2010, dir. Christopher Ray), Frogs (1972, dir. George McCowan), and Night of the Lepus (1972, dir. William F. Claxton). This led to watching good creature features (like The Thing [1982, dir. John Carpenter] and The Fly [1986, dir. David Cronenberg]) as well as zombie movies (like Night of the Living Dead [1968, dir. George Romero]) and ultimately many more horror movies. I came to horror quite late and quite afraid of it – it took me years to watch Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974, dir. Tobe Hooper), and I mostly watched it because you talked it up so much! For me, horror has always been tied up with community and friends.

CT: I think I came to it from the opposite direction you did! I was working with ecocriticism first (studying with Stacy Alaimo at the University of Texas at Arlington) and began my work on speculative fiction with science fiction rather than horror. My shift into horror came through creature features. During grad school, I started regularly watching terrible creature features with friends – e.g., Sharktopus (2010, dir. Declan O’Brien), Megashark Vs. Crocosaurus (2010, dir. Christopher Ray), Frogs (1972, dir. George McCowan), and Night of the Lepus (1972, dir. William F. Claxton). This led to watching good creature features (like The Thing [1982, dir. John Carpenter] and The Fly [1986, dir. David Cronenberg]) as well as zombie movies (like Night of the Living Dead [1968, dir. George Romero]) and ultimately many more horror movies. I came to horror quite late and quite afraid of it – it took me years to watch Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974, dir. Tobe Hooper), and I mostly watched it because you talked it up so much! For me, horror has always been tied up with community and friends.

Ecohorror as an academic focus grew out of ASLE 2013 in Lawrence, KS. I presented on Night of the Lepus and Frogs, and I attended the panel on ecohorror (also including Steve Rust, Joe Heumann, and Robin Murray) where you presented on The Birds (1963, dir. Alfred Hitchcock) and Night of the Living Dead. Although I was already presenting on creature features at that conference, it wasn’t until talking with you and Steve afterward that I started thinking of these movies as part of a larger conversation or a genre with a name. That meeting led to my involvement with the ISLE cluster on ecohorror that you and Steve co-edited, too, and since then it’s been a major thread in my research.

CS: Since you approached ecohorror from the science fiction side, I imagine you teach different types of courses than I do – built around different texts, I mean. I know for certain you incorporate a wider array of media forms into your classes than I do, bringing in literature, film, comics, real life, etc., whereas I teach film studies courses only. What role does ecohorror studies play in your teaching?

CT: Yes, I’m definitely always trying to incorporate a range of media in my courses. In general, since I teach STEM students (no English majors, film majors, humanities majors, etc.) and mostly lower-level general education courses, I have some clear constraints – but also a lot of freedom. And that allows me to work ecohorror into a lot of my classes! For instance, I often teach a 100-level general education Introduction to Humanities course (which requires a focus on more than one humanities field and thus encourages a wider array of media), and one option I’ve taken is to make it about fear and include a section on ecohorror. I also teach some environmentally-focused courses (Environmental Ethics & STEM and Environmental Literature & Culture), and I always incorporate ecohorror into those courses.

I think, as you’ve said earlier, that ecohorror is a useful mode for understanding our times, and so it’s an important topic to cover with students, whether the course is environmentally focused or not. They may not always like the texts I’ve chosen (some students just don’t like being scared), but they find the topic engaging. They find the questions it raises interesting – What fears do we have of nature? Why do we fear nature? How does nature fight back? What real-world consequences does this fear have on the natural world? – and we are able to shift from there into larger discussions of environmental issues like pollution and climate change.

Is your experience similar? Your student body is a bit different than mine. How does that influence students’ responses to ecohorror or your ability to incorporate it into your courses?

CS: I teach mostly undergraduate film courses, both lower-division general education type courses (e.g., a two-part survey on Film History) and some upper-division electives. I have no majors of my own – Film Studies is a minor within the English Department. So while I tend to have a strong core of film enthusiasts completing the Film Studies minor at any given time, my main job is to offer courses that work okay as electives for a wide array of students. One of my key courses is Ecocinema, an upper-division elective that works as a survey of several broad ecocritical themes, e.g., the pastoral, wilderness narratives, wilderness and gender, wilderness and race, the human/animal boundary, cyborgs, etc. I have included some ecohorror in that course (e.g., The Last Winter [2006, dir. Larry Fessenden] and, of course, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), but that is not the main emphasis, and I usually don’t include much horror in courses without “horror” somewhere in the title.

CS: I teach mostly undergraduate film courses, both lower-division general education type courses (e.g., a two-part survey on Film History) and some upper-division electives. I have no majors of my own – Film Studies is a minor within the English Department. So while I tend to have a strong core of film enthusiasts completing the Film Studies minor at any given time, my main job is to offer courses that work okay as electives for a wide array of students. One of my key courses is Ecocinema, an upper-division elective that works as a survey of several broad ecocritical themes, e.g., the pastoral, wilderness narratives, wilderness and gender, wilderness and race, the human/animal boundary, cyborgs, etc. I have included some ecohorror in that course (e.g., The Last Winter [2006, dir. Larry Fessenden] and, of course, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), but that is not the main emphasis, and I usually don’t include much horror in courses without “horror” somewhere in the title.

In spring 2020 I had the privilege to teach a full-blown ecohorror cinema course, a kind of dry run for the ideas that shape my in-progress book on ecohorror films. That course went very well, mainly because the students were great but maybe also because I chose accessible yet (I think) provocative films like The Birds, Jaws, Frogs, David Cronenberg’s The Fly, The Descent (2005, dir. Neil Marshall), and Annihilation (2018, dir. Alex Garland). As might be expected, the course frayed a little near the end due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and our need to suddenly switch to online meetings. Yet the course’s core ideas – organized around seven ecohorror tropes/themes such as revenge of nature, animals and meat, petrohorror, mad science, etc. – seemed to click for the students.

CT: Those core ideas seem like they would work so well, and that’s a great list of films to include. As a follow-up, then, do you have a favorite ecohorror text to teach? What works best for you in the classroom?

CS: I’ll focus on a few of the greatest hits from my previously mentioned ecohorror cinema course. First, The Ruins (2008, dir. Carter Smith) is a standout because we so seldom see plant horror (especially compared to animal horror or even microbial species/pandemic horror), and the plant monsters in that movie are truly uncanny/scary due to some excellent sound design. Thematically, the film interweaves its uncanny plant antics with a concise critique of Euro-American tourism in Latin America, framing the protagonists’ adventures as colonialism/racism and the protagonists as perhaps well deserving of the horrible fates they suffer. Like so many rural horror films, The Ruins also features abundant Ecological Indians, an element that helped my students connect the dots between colonialism and the revenge-of-nature ecohorror on display here.

Another high point in terms of generating class discussion was The Perfect Storm (2000, dir. Wolfgang Petersen), which of course is not a traditional horror film, though it counts as a kind of small-scale disaster film. It plays out mainly in the melodramatic mode, not the horrific one, though the Andrea Gail crew’s final death scenes by drowning are, of course, horrifying. (Also, there is a spooky, undead quality to George Clooney’s final moment onscreen in that film, as he draws back into the ship’s cabin to go down with his vessel, like a possible reverse homage to the Ben Gardner’s boat scene from Jaws [1975, dir. Steven Spielberg].) But the students understood the ecohorror angle and the best part of our class discussion was when we realized that the film’s early scenes of swordfish parts being weighed and hauled away while human characters talk about other stuff in the foreground were as horrifying as, say, similar scenes about cow feedlots in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. The sheer disregard for nonhuman life, the commodification of these fish by characters melodramatically framed as noble working-class heroes, is itself ecohorrific.

An early scene from The Perfect Storm in which humans discuss money matters amidst piles of swordfish carcasses – which they ignore.

CT: I love these choices! I haven’t taught either of these films and now I’m thinking about where I might include them in my own classes. You mentioned Jaws in passing, too, and that’s one of my favorites to teach. It raises such interesting issues of how the representation of nature can have a real-world impact (such that Peter Benchley says he regrets writing it), plus it’s still a really compelling film. In fact, my students have typically never seen it before and are shocked that such an “old” movie is so exciting.

Another film I love teaching as ecohorror is The Witch (2015, dir. Robert Eggers). Instead of centering a monstrous animal (Black Phillip aside), it locates its horror in an environment: the woods. It also fosters great conversations about the connections between ideas about nature, gender, and religion. The forest is horrific for the characters in the film, linked to the devil and to Thomasin’s insubordination and unhappiness; the forest is also, however, a source of freedom for Thomasin and the witches, a space outside the constraints of Puritan religion. This is also a movie that seems to have a significant impact on students – I have had one student tell me months later that she was still haunted by it. To me, this means The Witch is a successful horror movie, but it might be something to be mindful of when teaching it.

CS: I should add that yes, Jaws is an excellent teaching film and it is really an exemplary, foundational work of ecohorror cinema. Whereas Frogs and Jaws traffic in similar themes, basically capitalism vs. nature run amok, my students struggled with Frogs due to its somewhat low production values – not a problem for them with Jaws. It has aged well and, as you say, is still exciting.

The shark (known by the film crew and fans as Bruce) attacking the boat in Jaws.

CT: Turning from teaching to scholarship, co-editing Fear and Nature was a very collaborative process since we worked together on all parts of the project over the long period of time that publishing a book requires. How would you describe our collaboration, both its beginnings and the overall process?

CS: I’d like to start my response to this on a biographical note and share a memory of when I first met you at ASLE 2013 in Lawrence, KS. I was there presenting on The Birds (the piece that eventually went into the ISLE ecohorror cluster to which you also contributed). In fact, the idea for that cluster was hatched by me and Steve Rust on the shuttle bus back to the airport from the University of Kansas campus at the end of that conference. So that was a very fertile time to be thinking about ecohorror and science fiction. Robin and Joe were on that panel and Bridgitte was there with you. Anyway, that was a fortuitous meeting. I knew even at the time – you may have even said something like this or it was just apparent from how engaged you were in similar stuff – that we would cross paths again. We have since crossed paths many times and have worked together regularly, to my benefit.

So the current collaboration, the one that led to Fear and Nature existing, was in some ways an extension of conversations and collaborations we have been having since 2013 – e.g., conference panels, an MLA roundtable, contributions to each other’s special issues (in addition to the ISLE ecohorror cluster, there’s also a forthcoming issue of Science Fiction Film and Television on creature features and environment) and edited collections. That said, this was a whole new level of sustained collaborative work for me. It’s my first such project of this scale, and I have been extraordinarily lucky to have you, with previous experience editing an anthology plus a willingness to take point, to guide me through each of the many, many steps. To take one small example, I have never indexed a book before. In truth, that was a fun, conceptually interesting task once I got the hang of it. But I was glad you’d done it before and could lend a guiding hand.

CT: Ah, indexing. I’m sure many of our readers have been through that as well and understand the challenge it poses. Indexing aside, I have discovered through this project and my co-editing with Bridgitte Barclay that I really love collaborative work like this. I feel confident in my abilities to carry a project through on my own at this point, but I really love having someone to work with. And it’s not just about sharing the labor, because creating a book is always a lot of work (and co-editing is an additional layer of work). Instead, the best part of co-editing for me is generating ideas together and knowing that the final product will be richer for having more than one perspective. For instance, I know that some of our chapters and our introduction benefited specifically from your expertise in film studies and your attention to both those elements of the conversation and to specific filmic details.

I don’t want to romanticize collaboration too much. It’s still work, and it’s important to have someone you both trust and like to collaborate with. Having said that, though, I think it’s something everyone should learn how to do and that it’s particularly relevant skill for those of us in the environmental humanities. The environmental questions and issues raised by the field often require collaborative effort to address, so it only makes sense to practice collaboration in our scholarship, too.

CT: To wrap up, I’d like to ask you to consider the relevance of ecohorror to ecocritics and environmental humanities scholars. Although there is a growing interest in ecohorror, it’s not something all environmental humanities scholars already work with. How do you think our book – and the field it represents – might fit into others’ scholarship, teaching, or even lives?

CS: I would emphasize, as our anthology’s introduction and content does, ecohorror’s status as a mode rather than a genre. I think this is the most useful conception of ecohorror, as a modular set of tropes and tones that we find in a wide array of texts across almost every genre. Thus, ecohorror (or the ecogothic if you prefer) is useful not just to those of us who love and study horror-as-genre but to potentially all ecocritics. Horror and fear deriving from humans’ relationship to the nonhuman world is pervasive these days – in media and in real life – so the tools used and explicated in Fear and Nature are tools all of us can take up in order to better comprehend – and, if we’re lucky, heal – our world.

This image from The Witch illustrates common attitudes toward the natural world as something sinister and separate from humanity.

CT: That is such a great answer. I would reiterate the power of understanding what we fear. Fears of the natural world (at least in Euro-American culture) aren’t new. We can look back to the Puritans’ arrival in the “hideous and desolate wilderness” described by William Bradford, for instance, as a reflection of that fear, and this ecophobia (see Simon C. Estok) continues into the present. Many fears of wilderness or creatures (I’m thinking again here of the way Jaws prompted fears of great white sharks) grow out of ignorance, however, so identifying those fears and choosing to learn more about what we fear can be one powerful technique for environmental action.

The focus of Fear and Nature isn’t environmental education, but the chapters included offer another approach to these fears. They show that ecohorror can offer more than an ecophobic sense of the natural world as our enemy; instead, ecohorror often provides spaces to consider connections between human and nonhuman and prompts us to reconsider our attitudes toward the natural world.

Carter Soles is Associate Professor of Film Studies in the English Department at SUNY Brockport. He has written on the cannibalistic hillbilly in 1970s slasher films for Ecocinema: Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2012), environmental apocalyptic themes in 1960s horror for ISLE, and petroculture, gender, and genre in Mad Max for Gender and Environment in Science Fiction (Lexington Books, 2019). He is co-editor of Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene (Penn State UP, 2021) and is writing a book on ecohorror cinema.

Carter Soles is Associate Professor of Film Studies in the English Department at SUNY Brockport. He has written on the cannibalistic hillbilly in 1970s slasher films for Ecocinema: Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2012), environmental apocalyptic themes in 1960s horror for ISLE, and petroculture, gender, and genre in Mad Max for Gender and Environment in Science Fiction (Lexington Books, 2019). He is co-editor of Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene (Penn State UP, 2021) and is writing a book on ecohorror cinema.

Christy Tidwell is Associate Professor of English & Humanities at the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology. In addition to co-editing Fear and Nature: Ecohorror Studies in the Anthropocene, she also co-edited Gender and Environment in Science Fiction (Lexington Books, 2019) with Bridgitte Barclay and has published on ecohorror in ISLE, Posthuman Glossary (ed. Rosi Braidotti and Maria Hlavajova), and Gothic Nature.